What we mean when we say “Be Bold”

The arrival of the internet is the most impactful technology-driven change since the industrial revolution. Amidst such upheaval, defending the status quo is riskier for organisations than experimenting with new ways to serve their users, even if many of those attempts fail.

Which is why we advise our clients that the best way to reduce risk is by being bold.

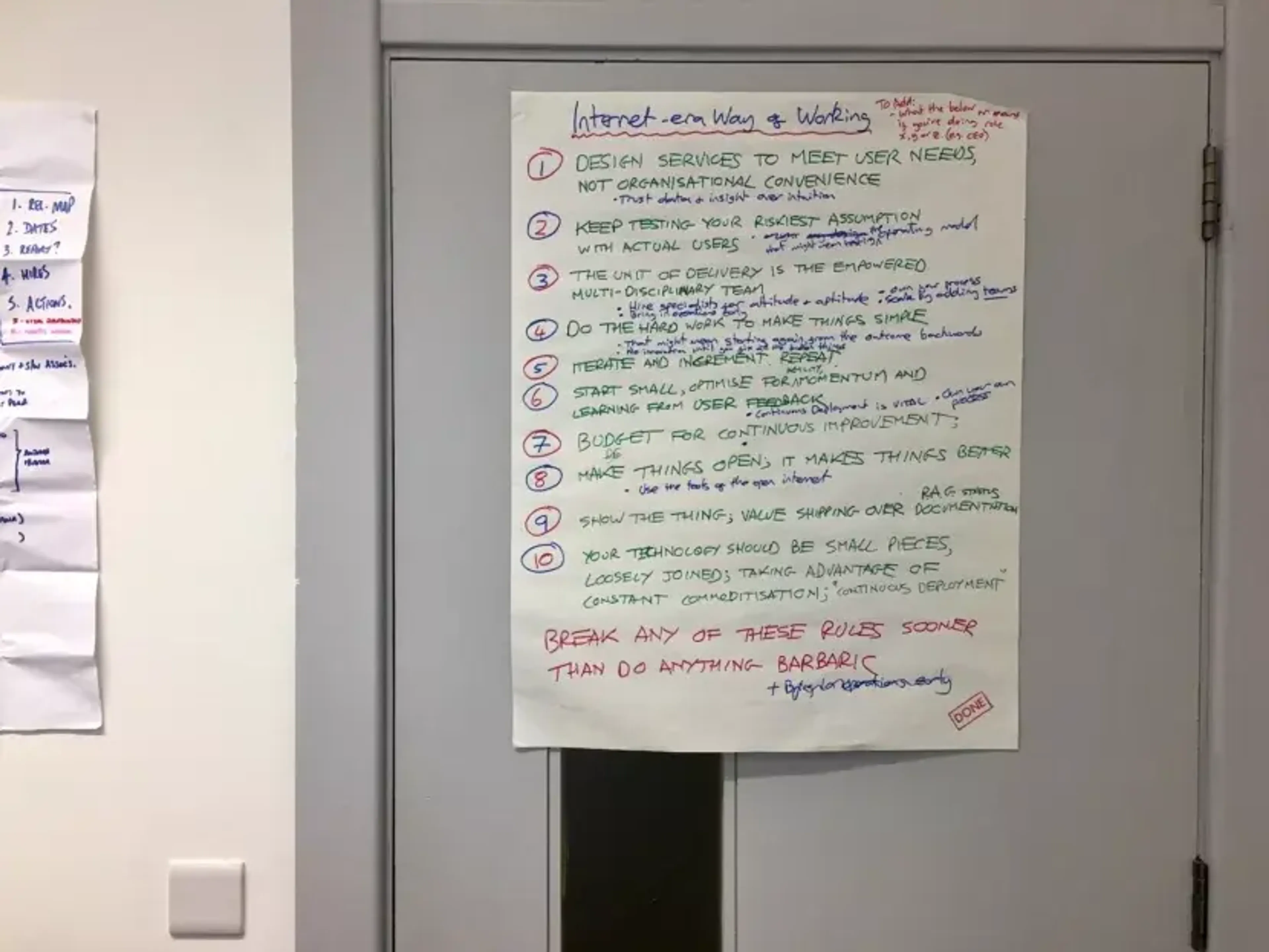

That means being bold in changing how they work. We point them towards our pamphlet The Radical How, our blog post on internet-era ways of working and Janet Hughes’ piece on making boldness an explicit value in the UK civil service.

So, yes to more boldness in how you work.

But that leaves what you work on.

I believe there are two types of boldness when it comes to what your organisation does:

1. Incremental boldness: Improving your existing services to make them better for everyone.

2. Exponential boldness: Reimagining your services, in ways previously unimaginable.

The UK government has focused on incremental boldness, using digital to improve its existing public services.

Meanwhile, the Indian government has focused on exponential boldness, aiming to create entirely new forms of digital public infrastructure, to benefit its society and economy as a whole.

So, while the UK has developed GOV.UK Pay to make it easier for their existing public services to accept payments from citizens, India has utterly transformed its entire payments landscape with its UPI platform.

Why does this matter? Well, the difference between both the ambition and impact of GOV.UK Pay and UPI is several orders of magnitude.

And UPI isn’t India’s only example of such exponential boldness. The Aadhaar biometric ID scheme is relied on by the public and private sector alike, with over 1.3bn issued to date, saving an estimated $27bn. Meanwhile the UK requires citizens to remember dozens of different logins for its digital public services.

So why the different approaches of India and the UK?

The answer is simple: context.

A more technocratic India saw the opportunity to leapfrog, and was willing to make big digital bets to try to meet the basic needs of its rapidly growing 1.4bn population. Why seek to digitise paper-based public services which few Indians trusted, and which in many cases hadn’t changed since the era of colonialism?

As a wise friend put it, “Aadhaar changed everything. It changed both what citizens could expect from the state but it also allowed us to dream that we could improve the lot that history led us to. That we have the power and means to change our trajectory.”

And the UK? Its incrementalism could be blamed on Brexit distractions, Whitehall departmentalism and the lack of technological literacy at the top of the civil service. Or a widespread austerity mindset that’s obsessed with making the as-is a bit more efficient, while dismissing any notion of investing to transform.

What’s undeniable is that a myopic focus on incremental improvement of existing public services has trapped the UK in a local maxima. UK public services desperately need an injection of exponential boldness, as described in Richard Pope’s wonderful new book.

But you’d be wrong to assume India doesn’t have its own challenges. The political leadership that has pushed this exponential boldness is and has been, well… fearsome. Opposition to the likes of UPI and Aadhaar has not been brooked, and it is far from clear that the necessary civic checks and balances have been developed to govern such potentially all-knowing platforms on behalf of each and every citizen.

Digital technology challenges and changes societies - not least democracies - in ways we are yet to fully understand. India has moved incredibly fast; let’s hope they’ve not broken anything fundamental.

But I still think the balance of risk now points strongly towards more exponential boldness.

In the UK, the way the NHS helps people manage chronic conditions is ripe for some exponential boldness, albeit done with care. The NHS could pivot to supporting millions living with the likes of diabetes, COPD, AMD or IBD by continually monitoring their condition remotely, pointing towards radically better care at lower cost. Scaling up such exponential boldness is likely a better bet than digitising an existing 3 monthly outpatients checkup service.

This analysis also applies to the private sector. Netflix started out by digitising an existing DVD rental business. That doubtless felt pretty bold at the time, but it was nothing like the boldness required to take full advantage of the shift to streaming. The results were exponential, but so was the change in pretty much everything Netflix did.

Note there’s nothing intrinsically better about exponential boldness, merely that its potential long-term impact is, well, exponentially greater - for good or for ill. Exponential boldness is crunchy.

But customers and citizens will always expect more. And while incremental boldness might buy time, leaders must help their organisations imagine the previously unimaginable, not just improve what’s always been.

In the long term, only those institutions which learn to harness exponential boldness are going to thrive. Technological revolutions do that to institutions.

Written by

Tom Loosemore

Founder