Claire Bedoui

Director

Emily Middleton worked as a Partner at Public Digital from September 2018 until July 2024 and set up Public Digital’s international practice, working with multilateral development banks, UN agencies, and philanthropies.

This article was originally published by the Harvard Ash Center. It was written by David Eaves, Emily Middleton, Claire Bedoui, Rohan Sandhu.

Each year, David Eaves of the Harvard Kennedy School and Public Digital convene digital service groups from over 30 governments around the world. Last June, digital government leaders stressed the need to rethink funding models for long-term impact. In recent months, donors have made new commitments to support global digital public goods. The covid-19 pandemic has precipitated a significant push in this space, forcing governments and societies to turn toward digital technologies to respond to the crisis in the short-term, resolve socio-economic repercussions in the mid-term and reinvent existing policies and tools in the long-term.

As a follow up to the aforementioned June convening, we hosted a closed-door roundtable in December 2020 for donors in the digital government space, as an opportunity to have funders connect and share their strategies and theories of change. The goal was to foster more connections between the players as well as discuss what has been learned, the pros and cons of different approaches, identify opportunities for the future and access how donors transform their own ways of working.

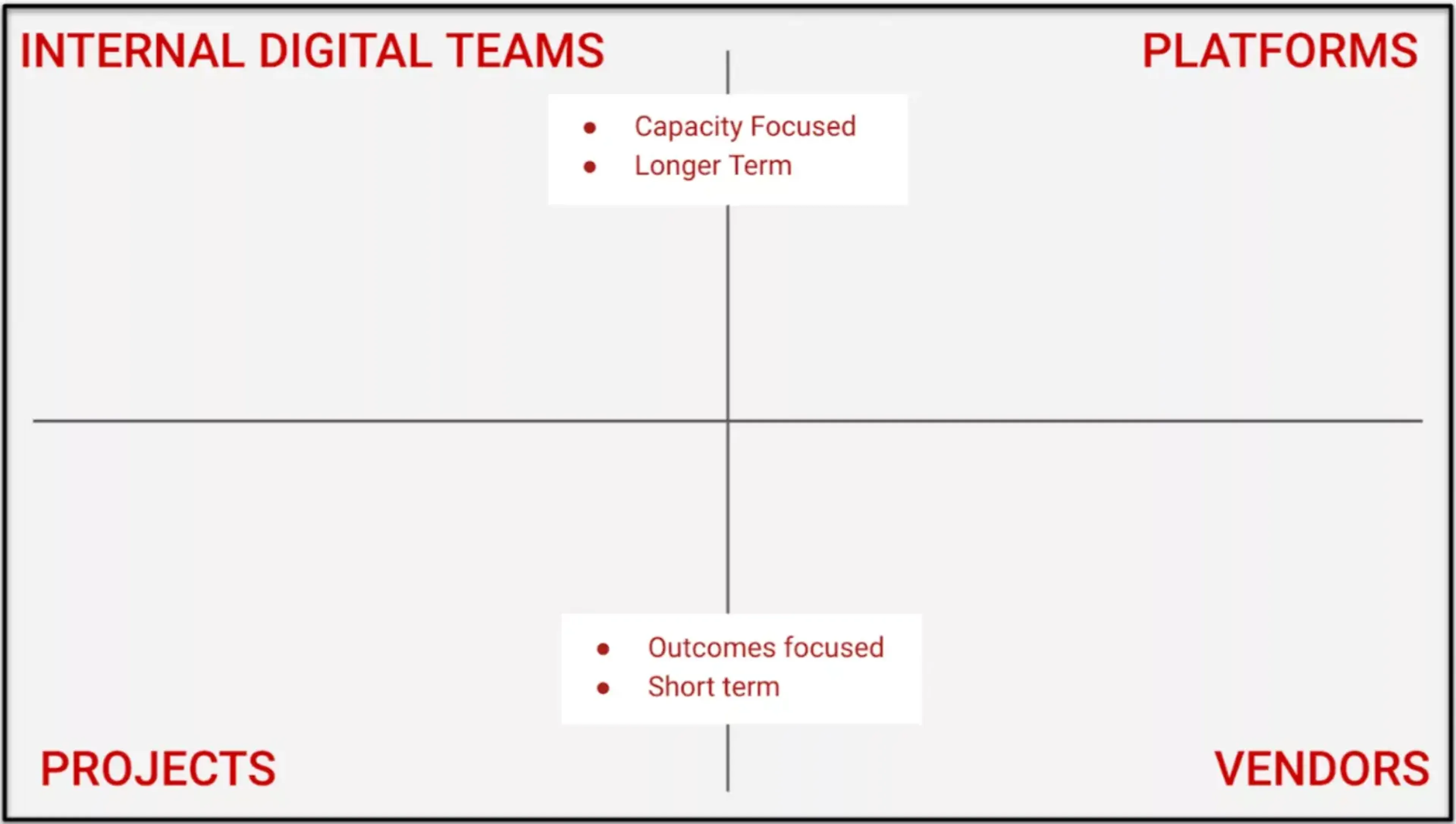

To help structure the conversation, funders were presented with a simple model developed by David Eaves and Lauren Lombardo at HKS. It attempted to reflect the two broad sets of choices funders of digital government confront: funding internal digital teams versus vendors, and funding multi-sector platforms versus specific projects (represented by the 2x2 matrix below).

Historically funders have tended to finance sector-specific projects implemented by vendors, like an electronic healthcare records system or a tech-based education platform. However, over the past few years, there has been increased interest and experimentation with other approaches. These include:

In other cases the shift has been more complicated — for instance, India’s Aadhar started out as a relatively narrowly-focussed project implemented by a vendor (iSPIRT), but expanded in scope to serve as a general ID platform that enables both public and private digital services across the country.

There is evidently a progression in the sector towards both scale and sustainability. The shift to platforms allows potential benefits to be shared by a larger number of government departments. Internal digital teams help address sustainability concerns by trying to ensure continuity after external vendors leave, and an evolution in governments’ own capabilities to deliver these services.

The funders we convened represent this evolution, with a bias to multi-sector or cross-government digital platforms. In a pre-roundtable survey of participants, we asked funders what they would prioritize between these four options: 64.7% of the 19 respondents selected multi-sector platforms and another 29.4% chose internal teams. Nearly 88% of funders said they were already funding multi-sector platforms. One funder encapsulated this shift as follows: “we are now investing in a broader way. Earlier, we had projects in e-agriculture, e-health, e-education, e-something, but we now recognize that without addressing ecosystem and collectivity problems, including regulatory frameworks and data protection, we won’t end up anywhere.”

This is in line with the World Bank’s rationale for its new GovTech approach:

“Early digitization projects were often sector-specific, uncoordinated efforts that led to islands of excellence in some cases and inefficiencies in others. GovTech promotes a vision of integrated e-government facilitated by digital solutions that simplify procedures, are more accessible to citizens, and that are accompanied by policies that promote greater transparency. GovTech represents a fundamental shift in the World Bank’s approach to digitization, leveraging expertise across different sectors to support whole-of-government public sector modernization that results in tangible outcomes for client countries and beneficiaries.”

But even as funders see the value in taking a more integrated approach instead of a piecemeal sector-specific one, they don’t necessarily have a clear strategy. Less than 30% of funders expressed confidence in knowing what works and having a clear strategy. 23.5% have an initial hypothesis of what might work, while another 23.5% say they are learning but still don’t have a clear strategy. And 17.6% have been experimenting by funding a range of different interventions.

Funders attribute this to challenges on both the demand and supply sides. On the demand side, governments need to think more holistically, but inherent silos and a complex array of institutions, agencies, and stakeholders all playing different roles can impede this. Thus, while building the internal capacity of government, it is critical to establish or strengthen central teams that can coordinate across government silos and set up cross-cutting platforms. As one funder stated, “this has the greatest bang for the buck,” but highlighted a variety of institutional barriers that can prevent success. For instance, in some contexts, a Chief Digital Officer hired from the private sector has to be paid in accordance with government pay-scales, while in others contexts the role has become overly political.

The lack of a holistic approach is as much a problem on the supply side — a large number of multilateral donors and private foundations are siloed based on sectors that prevents an integrated approach to funding. Some organizations (like the UNDP and the IDB) have recently made organizational changes to address this issue, establishing digital teams with a cross-organisational mandate. The UNDP has also invested efforts to recalibrate its internal technology and data architecture, revamping legacy IT, building new ERP systems, and setting up data back-end services, which were earlier fragmented into different silos.

But even beyond this, the quantum of funding required for such large-scale projects necessitates a pooled approach, especially among philanthropists. According to one discussant, funding open-source infrastructure is not a priority for either governments or multilateral and bilateral donors, which makes it a gap that needs to be filled by philanthropists and private foundations. But these are big-dollar and long-term commitments. The need to establish pooled philanthropic vehicles emerged as one key opportunity for funders to address this funding deficit.

Funders also find that it is critical to demonstrate the value of a building-block approach, wherein the outcomes of donor-funded programs complement each other to fulfill the roadmap of the government. As a recent report by the Digital Impact Alliance (DIAL) notes, “In Ethiopia, the government benefited from the help of various development partners to identify the main building blocks the country needed to kick-start its digital transformation. It resulted in a clear roadmap aligned with a digital economy reform agenda and development plan.”

Ultimately, there is wide recognition that covid-19 has accelerated the demand funders have experienced from governments to support digital services. Governments that previously invested in their digital capabilities were able to ramp up their response more efficiently. Moving forward, there is growing consensus around investing in digital infrastructure — the layer above the “pipes,” or the common infrastructure that can be leveraged across the public sector.

We look forward to updating everyone on future discussions. If you are a funder and are interested in being a part of these conversations, please reach out to us to be included.

Director