Audree Fletcher

Director

Most people recognise “economies of scale” intuitively.

It happens when they bulk buy at the supermarket to pay a lower per unit price, when they rationalise offices to reduce real estate overheads, or when their organisations agree to share HR services.

Scale economies are the savings or additional margin that we chase when we centralise, merge, pool, share and aggregate. They can be deliciously visible and quantifiable compared to, for example, brand value.

The problem is that the logic of scale economies is so thoroughly baked into modern management culture that we’ve forgotten how to think critically about it.

Scale isn’t always, and automatically, a good thing, and in fact it can produce diseconomies of its own. Bigger is not universally better.

To ensure the survival of their businesses, leaders grappling with digital transformation need to consider the sources of scale diseconomies. Below I examine two common examples:

Language like “human resources” and units like FTE reveal the tendency of some managers to think of people as company assets, the way they might think of buildings and heavy machinery. The economic rationale for scaling your workforce is that you can increase productivity by spreading overheads/fixed costs across more employees, and through better division of labour and greater specialisation.

But that logic only takes you so far because it fails to account for the fact that your workforce is made up of humans, not widgets and the assumptions you apply to each are not the same.

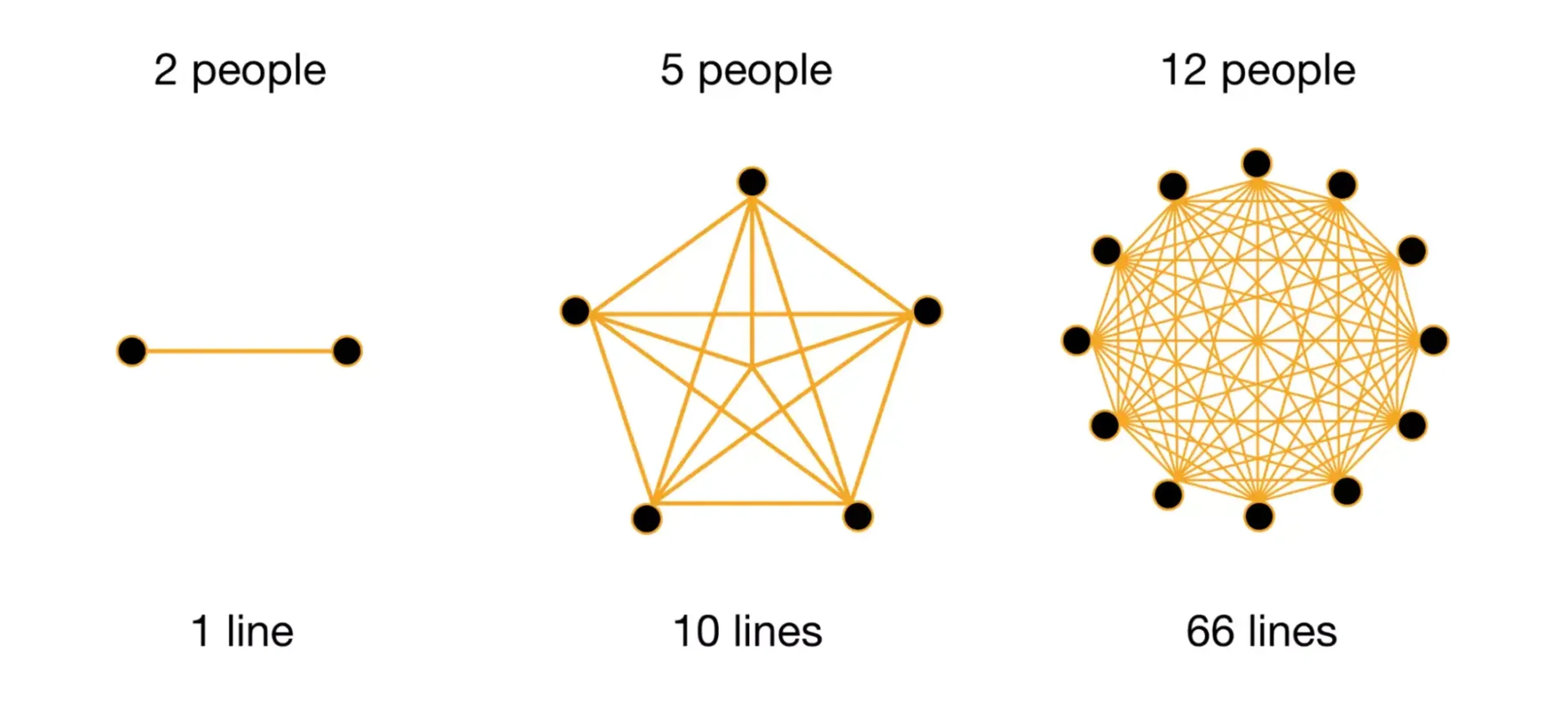

The difference is that humans need communication, and that doesn’t scale linearly. The more people you have working together, the more lines of communication you need to keep people aligned, to collaborate and deliver together, to ensure they feel invested and included. The transaction costs or “communication tax” - represented by the lines of communication in the diagram below - grows disproportionately as you add more people. Far from increasing productivity, beyond a certain level adding new people will introduce inefficiency.

Similarly, relationships and culture don’t scale automatically, quickly or easily. Organisational culture is the secret sauce for many firms’ competitive advantage. But situations like fast growth, or corporate mergers, often fail to deliver all the benefits imagined from them because leaders underestimate just how hard and slow it can be to bring groups of people together, and have them feeling and acting as one team.

More people usually means more projects and more complexity and dependencies. This creates greater risk and increases the need for management. Eventually you have to add more management - more “overhead” - because if you spread this too thinly it creates bottlenecks and throttles productivity.

In brief, diseconomies of scale are extremely common when it comes to scaling people, so think critically about where more people might be a problem, not a solution.

Another instance where diseconomies affect teams in unexpected ways is in the drive to reuse, share or export a solution.

Many organisations now seek to achieve economies of scale and reduce perceived functional duplication by increasing reusability. This might be reusability of a model, a component, an approach, a product or a service. However, the presumption of reusability - irrespective of suitability - tends to result in a one-size-fits all approach, and sometimes, in a first-size-fits-all approach. This is where an organisation forces early convergence and lock-in to a solution for one context and then applies it everywhere else.

Of course, we know that something that tries to please everyone risks meeting the needs of no-one. Those for whom the imposed solution is a poor fit will find themselves with “debt” to be addressed (often design, organisational, technical debt). Remediating it comes at a cost (undermining the efficiency case); failing to address it forces staff and customers to create workarounds (increasing inefficiency in the system more widely).

Overall, it is much smarter to research, design and build a specific solution for a specific problem first. Focus on learning quickly what would meet user needs and deliver the outcomes you’re seeking, and then you can turn your mind to refactoring for efficiency.

The presumption of reusability in service of scale efficiency can be really harmful if not applied cautiously. One-size-fits-all by default, as a strategy, will close down design decisions too early and leave you with a suboptimal solution. Leaders need to give their teams space to identify the right thing to build first.

Economies of scale can be valuable. They can make and break the cost-efficiency of some operations. However, there are plenty of ways leaders can be caught out by diseconomies of scale.

We need leaders to pause and think a little more critically about where and why they’re seeking economies of scale. And we need to get better at identifying the limits of efficient scaling, like scaling workforces and reusability, if we want to avoid making counterproductive decisions.

As with all areas of your business, the success of your organisation’s digital transformation rests on understanding when bigger is better, and when it is not.

Director