Lina Dixon

Director

Service maps aren’t just tools - they’re catalysts for transformation. They clarify complexity, foster collaboration and enable informed decision-making. They help organisations navigate the challenges of transforming and continuously improving their services. We worked with Defra’s Farming and Countryside Programme (FCP) to develop a service map and a set of service outcomes.

The programme is responsible for managing the transition from EU agricultural subsidies to domestic schemes that promote sustainable farming, safeguard the environment, enhance biodiversity, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and maintain farm profitability across England. FCP is delivering one of the government’s largest transformation projects.

Our work with FCP led to an important realisation: the value of service mapping lies not just in the artefact itself, but in the conversations, relationships and consensus it generates.

While the map provides a clear picture of how services function, its greatest strength is the shared understanding it builds across teams.

Here’s how our work with FCP helped shape a more joined-up approach to service delivery:

As we started mapping the service, some recurring themes emerged — patterns that pointed to opportunities for improvement.

These themes are common in large, complex programmes. What stood out in this case was the willingness across the programme to work together to resolve them.

Defra's David Caldwell captured the shift well:

“Showing an organisation its map of services is like showing a budgie a mirror for the first time. They're like, 'Wait... I thought I was a dog'”.

The process of developing and refining the service map gave teams a new perspective. It helped create a shared understanding, reduce ambiguity, and build confidence in how the service fits together.

It took time and effort to bring senior policy and service designers together around a unified service map and shared outcomes, but doing so was essential to building the trust and clarity needed for lasting improvement.

Service mapping calls for transparency. By surfacing all the moving parts of service delivery, we were able to show the complexity of the system and start building a shared understanding across policy, operational and digital teams.

This transparency created space for honest conversations and helped build trust across the programme. The service map also became a practical tool. It helped teams avoid duplication and align their work. For example, when a new supplier joined the programme, the map made it easy to show how their role fit into the wider delivery landscape.

This kind of clarity and collaboration has been invaluable for FCP and the wider Defra group.

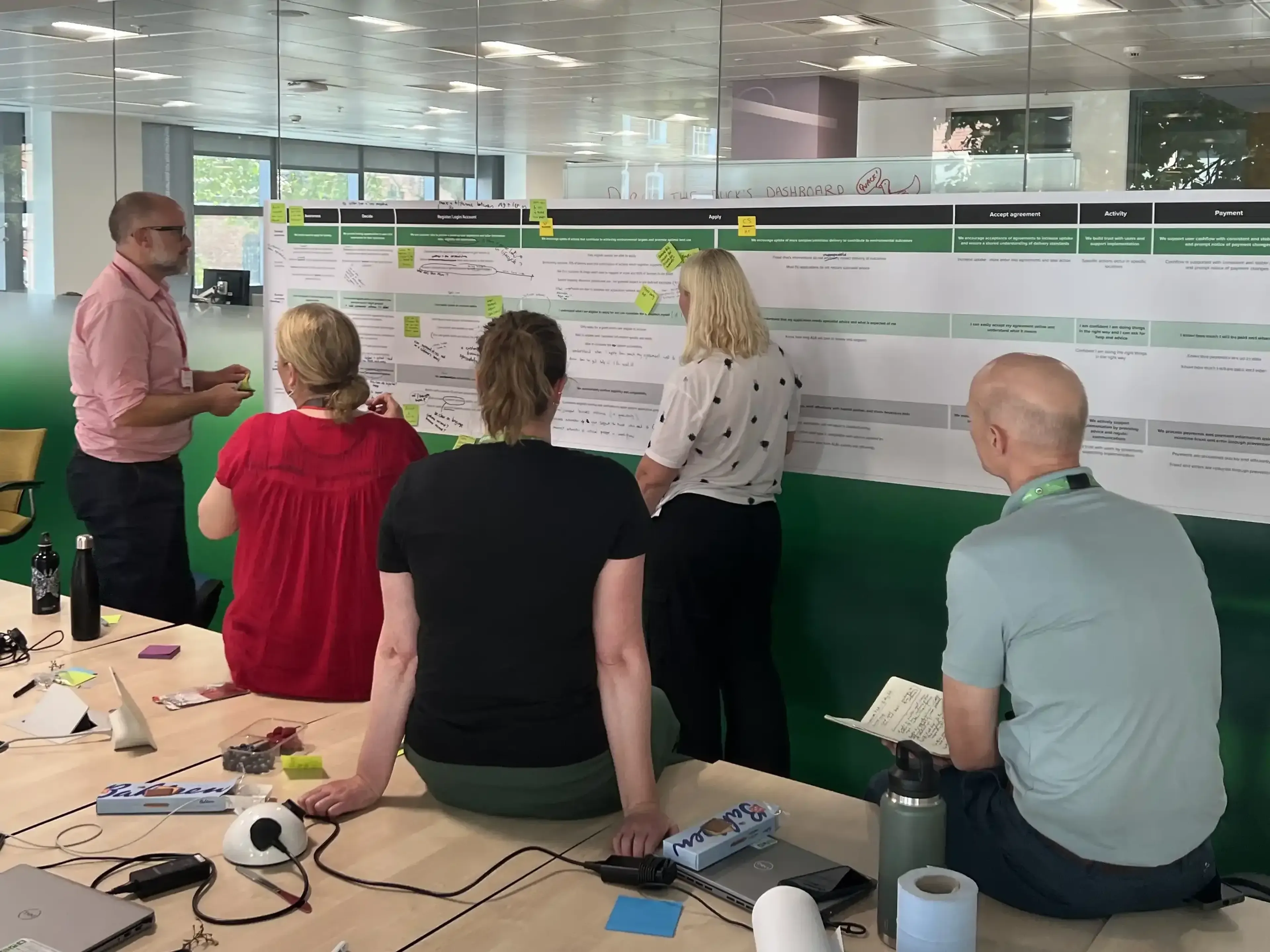

The FCP service map was developed over several months through a series of workshops and one-to-one sessions. From the outset, the team worked to include everyone involved in delivering the service, regardless of organisational boundaries.

We worked with stakeholders from across the programme, from policy to strategy. We also engaged with colleagues from the Rural Payments Agency (RPA) and Defra’s Digital, Data and Technology Services (DDTS).

This collaborative and iterative approach ensured the map reflected the realities of delivery as well as aspirations for improvement.

The service map reflected a large, complex system of interdependent teams and activities. To ensure it remained relevant, we created a shared model of ownership with clear responsibilities.

Senior leaders, such as deputy directors, were identified as accountable owners for different parts of the map. They were supported by practitioners responsible for keeping the map up to date.

This structure helped to embed the map as a living document, supporting day-to-day delivery and long-term planning.

We helped Defra design the map to support multiple audiences:

Service outcomes were central to this work. They provide a way to measure progress against long-term goals without prescribing specific solutions.

Outcomes describe the real-world change a service aims to deliver—linking user needs, policy intent and operational performance. They also help bridge the gap between leadership expectations and team-level delivery.

Working with senior leaders to align outcomes helped balance policy ambition with operational reality. And while different perspectives sometimes involve trade-offs, they aren’t necessarily in conflict and creative service design can often resolve the tension. Over time, the service can improve its performance across multiple outcomes.

Once agreed, outcomes and their metrics can support governance and performance tracking, while helping teams plan and prioritise their work.

We see service mapping as more than a one-off exercise. It’s an ongoing behaviour. The FCP experience highlighted the importance of:

Service map owners need to know who they should engage with, build relationships across relevant teams, and keep the map active and useful through regular updates.

Our work on the FCP service map is just the beginning. By embedding service mapping as a continuous practice, we hope to support deeper collaboration and more effective service delivery.

Service maps may start as artefacts, but their true power lies in the trust, clarity and transformation they enable. We look forward to keeping the conversation going.

Director

Network member