Tom Loosemore

Founder

A couple of weeks after leaving the UK Government Digital Service (GDS) back in October 2015, I attended the Code for America summit in California. I gave a talk about some work I’d led during my final months in government, work that explored what it would be like to live in a truly digital nation, with new digital institutions.

What follows is the gist of what I said that day. I’ve updated it for clarity, and added some links that I think will be useful. The talk lasted an hour; what follows takes a bit less time to read (but only a bit – it’s about 5000 words long – so get yourself a cup of tea before reading on much further).

It’s worth noting that this is my interpretation of the phrase “government as a platform”, which means slightly different things to different people, in different contexts. It’s not the same as Tim O’Reilly’s original, and it’s not the same as the current programme of work underway at GDS. It’s a fork of its own.

I’m posting this here, now, because it offers a useful marker as to where our thinking about the future of government lay when Public Digital was formed three years ago.

Since then, we’ve been building our government practice on these intellectual foundations. This work provoked many fundamental questions at the time, and continues to do so. I’ve added a few at the end – in the hope that some of you will be able to suggest answers.

I was one of the founders of the UK’s Government Digital Service (GDS), and spent about five years there helping the UK government understand what it means to be “digital”.

After I left, Code for America founder Jen Pahlka asked me to share what lessons I thought we’d learnt in the UK about what worked and what hadn’t worked. What had we missed? What would we do differently?

Truth be told, there’s only one message, one lesson that matters, so I’m going to focus on that. I’m going to talk about institutions. Notably, the need for new institutions to make the most of this digital revolution.

If you want a natively digital nation, or a state, or a city, or whatever, my message today is you actually need to be bold enough to create some new institutions; institutions that are of the internet, not on the internet.

As a starting point, they must be public institutions whose culture, practice, business models, skillset, ways of working, ways of thinking are native to the Internet era, not divergent to it.

What’s more, some of these new institutions need to be horizontal in nature, making high quality data or platform services like identity assurance available to public-facing services across both government, and – crucially – the private and 3rd sectors. Allied with this, new service-centric institutions are needed that make real-world experimentation the heartbeat of future government, where policymaking and service delivery are combined in an iterative journey towards better outcomes in practice, not just in theory.

So how did we reach this conclusion?

In the years following 2010, the UK government saw a lot of fast-paced change. One of the first things GDS did was replace hundreds of government websites with just one. It transformed dozens of fundamental services, to make them simpler, clearer and faster. It set up new procurement systems, and created a new identity assurance platform. It hired hundreds of digital people right across government, including some very senior ones.

The answer to Jen Pahlka’s question, “What was the big lesson?” was this:

We weren’t bold enough. We weren’t nearly bold enough. Not even close.

Why? Because iterating existing public institutions is not good enough. We have to create new ones. And that requires boldness and political capital.

A pile of paperwork sent through the post.

These days, it has changed. Now it looks something like this:

It’s all online now – well, most of it – but you still need to understand the structure, and processes, and ways of thinking of government to even make a start. You have to adapt yourself to the bureaucracy. To have your simple need met, you are expected to understand the mess of silos into which government has fragmented.

And our focus for most of our time at GDS was digitising that. Digitising bloated paper-based processes, and turning them into pixels.

That’s not to demean this work. It was an important and probably inevitable step, leaning on much often unheralded hard work that had gone before.

But we shouldn’t fool ourselves into thinking that we’re anything other than still at the start of a journey to the UK having natively digital government.

There’s a much, much bigger prize up for grabs. I believe that the first nation, or city, or state that creates new institutions with the values, sentiment, business models and culture of the internet is going to win big.

Not just because it will have better, cheaper, more efficient and more empathetic public services that meet user needs, but also because those institutions will provide a new foundation, a new digital infrastructure serving the whole of society. They will support new ideas in enterprise, culture and government that were previously unimaginable.

This is the Crossness Pumping Station on the south side of the River Thames in London. It is a triumph of Victorian engineering. It pumps sewage out of the city.

It was built by an incredible Victorian civil engineer called Sir Joseph Bazelgette. The pumping station was part of a much larger, more ambitious project to build a huge new sewer network for the entire city of London. It removed the risk of cholera. It made the streets clean, it improved sanitation, health, welfare, well-being.

Bazelgette’s work created a platform of civic infrastructure for London in the 1850s. From this grew the prosperity and trading dominance of the United Kingdom through the latter half of the 19th century. The British Empire grew in strength partly because the government at the time invested in revolutionary, radical infrastructure like this sewer network.

The pumping station, and the sewage network it was part of, were brand-new technology. Both were both commissioned by the Metropolitan Board of Works. This was a brand-new institution, very contentious at the time due to its remit, its funding model, its outlook and its mere existence straddling dozens of local authorities. It was established by an Act of Parliament and paid for by a tax on property owners. Its mission was to provide bold new infrastructure. It worked, helping to accelerate London’s rapid growth into a globally-dominant city during the industrial revolution.

We’re in the middle of the digital revolution. But have we built any new public institutions? Have we invested enough in new digital public infrastructure? I’m not sure I’ve seen enough. I’ve seen some existing public institutions do their best to adapt, but I’ve not seen enough new ones.

In early 2015, Richard Pope, Jamie Arnold and I went for a walk along the river from Erith to Greenwich, paying homage to Crosskeys en route. Richard is the most talented and public-spirited internet thinker I know, and much of the thinking that follows is his; Jamie lives and breathes digital delivery. They were the first two people I hired into GDS. Our conversation took the following turn:

“If there are going to have to be new institutions, we need to understand what shape they are, how they would relate to each other, what ways of working they might adopt? What would the institutional architecture look like for an accountable, digital nation? Not a nation that’s simply digitised existing paper silos, but a natively digital nation.”

To find answers to these questions, we set up a small team to learn by doing. For the record, that team was:

The team’s brief began simply: “Imagine the same broad political settlement existed, with central and local government. But everything about how they function is up for grabs, including lines of accountability.”

Then it set out some outcomes to aim at:

This team worked for about 12 weeks. They did amazing work. They sketched in code, only building just enough to help them understand the problem. They built prototypes – which I’ll come to later.

But if you asked someone to draw a diagram of where the team’s thinking ended up, they might draw something like this:

Think of it as a city, the buildings are public and commercial services. They’re supported by a new digital infrastructure.

This city is an ecosystem, a dynamic place. New services are being built, improved, duplicated and closed down all the time. It’s an environment where user needs are paramount, so services can change rapidly to respond to changing needs. New possibilities emerge.

That dynamism is made possible by layers beneath, starting with “common platforms”.

These are boring bits of infrastructure, really, that you should really only do once, using open standards. They do a lot of the heavy lifting.

(An example: right now, there are many ways for members of the public to pay money to government. Over the years, each department or service has procured its own bespoke way of accepting payments. Now, that’s changing: there’s a new common platform called GOV.UK Pay, which does that heavy lifting and makes it easier for service teams to process payments online.)

Moving down to the bottom of the diagram (we’ll come back to the “Trust and consent” layer in a moment), you see data represented by “registers”.

Data gets treated differently because it behaves differently. Software ages like fish, but data ages like wine. It should be looked after carefully.

Data is the new foundation of our digital nation. It should be authoritative, canonical, easy to test and check, and have integrity. And for personal data, only available to services that have gained the consent of the user or citizen.

A lot of data (not all of it, but a lot of it) should exist as reliable lists of information: registers.

A register is a single source of truth. It’s the only source of information about its subject matter. Before GDS created the country register, there were dozens of different lists of countries in use all over government. Service teams wanting to use a list of countries struggled to find out which list they should use, and which was most up-to-date. Now, the country register is the list. There is no other list.

Similar lists can, and should, exist for many things (schools, prisons, local authorities). Those, and many more, are under development now.

We called them “registers” because yet again, the Victorians got there first. They created the public bodies we now call Companies House and the Land Registry. Both were established in the paper era to do the same job as a modern digital register. Companies House maintains a register of all businesses in the UK. The Land Registry maintains the authoritative record of who owns what land.

The bodies that operate the new government registers are an example of the new kind of institution I’ve been talked about from the beginning. These registries, overseen by a person in charge (the registrar) take ownership of a particular register or group of registers. Parliamentary legislation makes them responsible for ensuring that each register is accurate and up-to-date.

Now let’s talk about that layer in the middle of the diagram I skipped over, the layer called “trust and consent.”

It’s not just about using technology that preserves privacy; it’s recognition that consent, understanding and trust are at the heart of a modern democracy and a modern government.

This layer represents institutional oversight. You need people there who make sure that everyone else in the ecosystem plays by the rules, and that citizens understand what’s happening to their data.

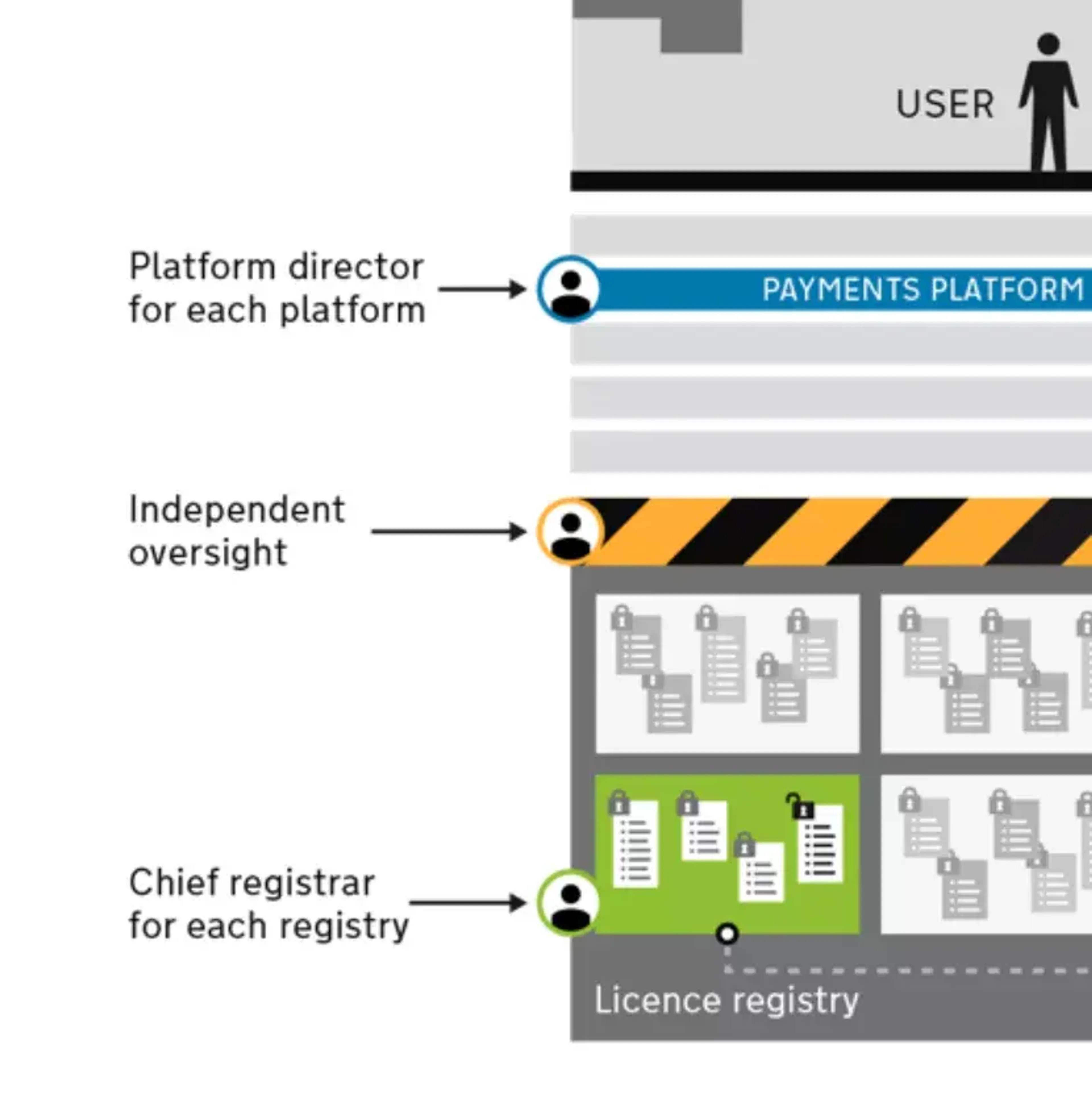

To explain trust and consent a bit more, let’s look at another view of the same model. In this 2D version, you can see individuals who work within the ecosystem.

Ministers are still responsible for their policy, that doesn’t change. There are also clearly identified service managers who are responsible, as civil servants, for each service.

And there are people in charge of platforms, working across many services.

Below, you have the data institutions I’ve already mentioned, the registries run by registrars.

At the trust and consent level, you see more people – independent overseers. I’d argue that they should be outside government, ideally reporting directly to Parliament and with a lifespan that is not beholden to an electoral cycle. They are there to make sure that the rules are obeyed and that bad things aren’t happening. They’d need proper funding and very sharp legislative teeth to enforce the rules.

OK, so I’ve spelled out the future we want. What would it look like in the real world?

Back in 2015, we made a short film that uses some of the prototypes built by the team, and explains how it all fits together:

(Read a transcript of the voiceover for that film.)

Some of the details in that film have been overtaken by events since 2015, but I hope you see the point it was trying to make: that platforms (things like identity assurance, payment, digital proof) and the notion of consent sit at the heart of it all.

Now I’m going to walk you through 3 example services that the team developed to make their work more relatable. (An apology in advance: this next section uses a series of screenshots that I took at the time, but they’re not all of the best quality. My fault. Sorry about that.)

Let’s look at another example. In the introduction to this essay, I talked about how difficult it is to set up a new business.

In this reimagined digital nation, you could set up a new business in just a few minutes. Not just a company in theory, but a company that can trade, a company that is set up to employ people, pay taxes, and seek official licences and permits for its activities, if necessary.

Ministers would love to have something like this. So would a lot of civil servants. But right now, the way government works in reality makes this unimaginable.

But let’s assume for a moment that it is possible, that we can do it. As a user setting up my own business, where would I start? What would I have to do?

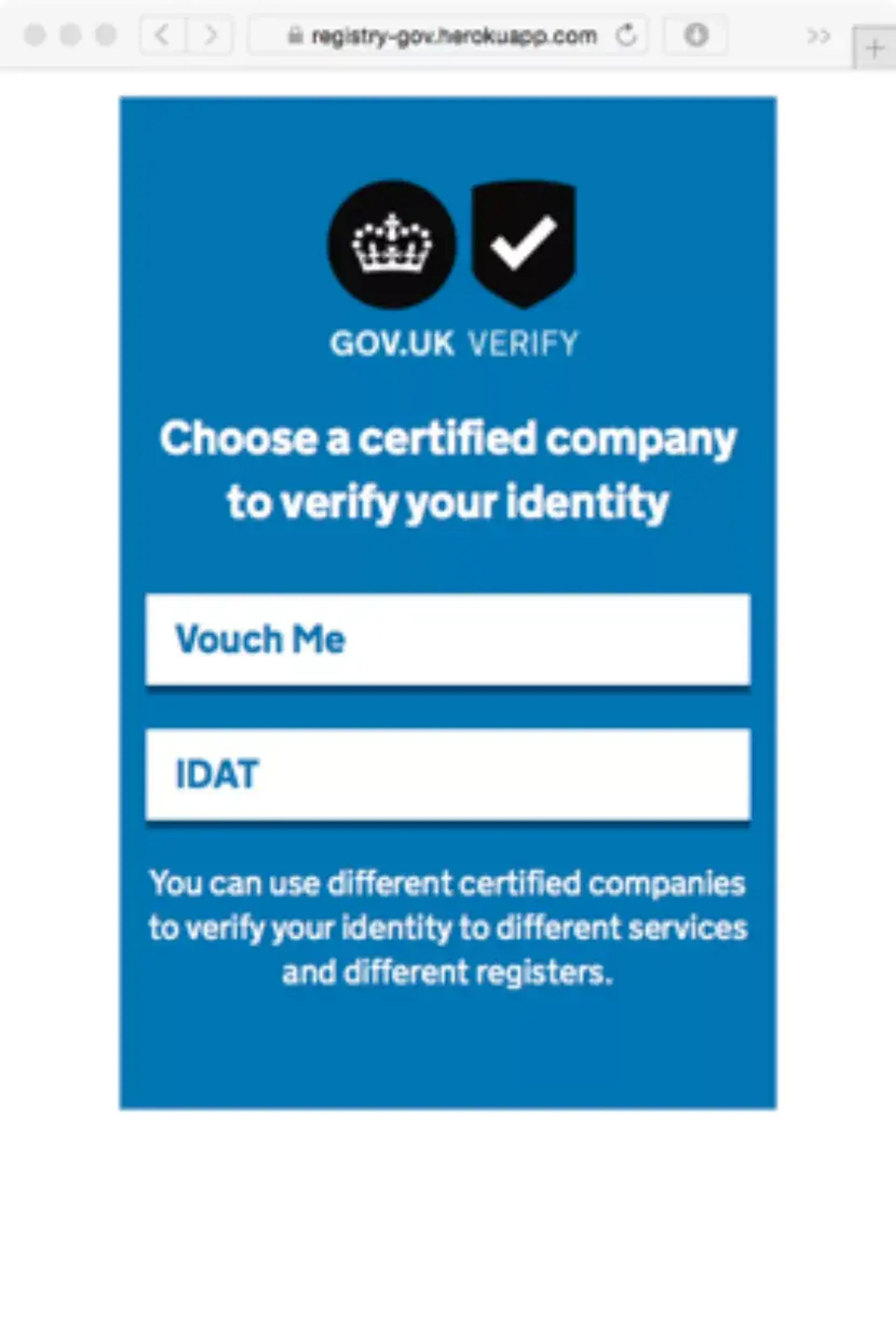

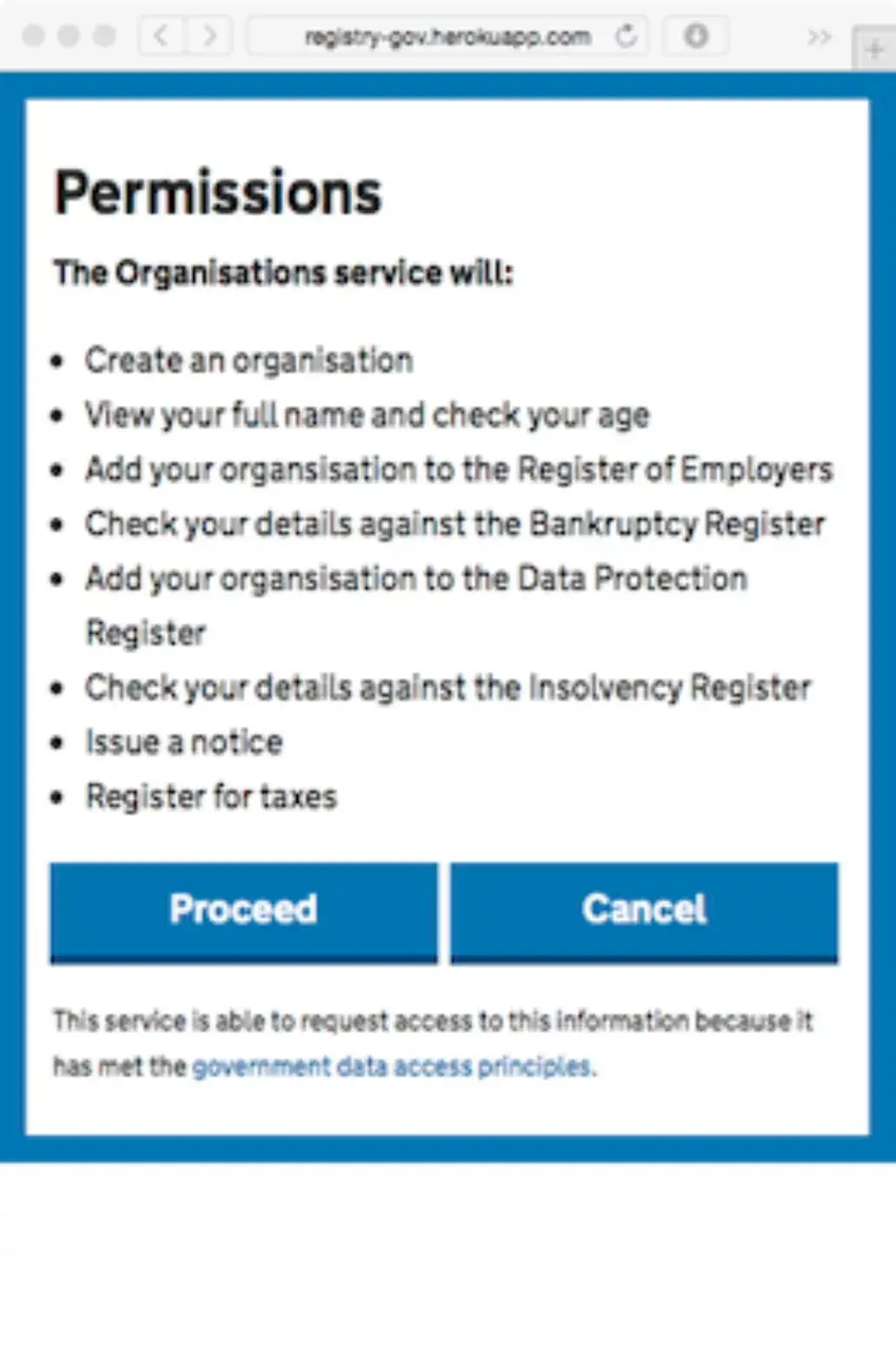

First, I’d be asked to prove my identity to an appropriate open standard, digitally. I’m then asked to grant permission for the service to access and edit data related to me or my company from government-curated data registers.

Immediately, I’m being asked to agree to quite a long list of things. That’s normal – these are the sorts of things you might well need to think about when setting up a new business. The service wants to know about taxes, so it can add me to the Tax Register. It wants to know my full name and my age, which it can get from my identity provide, as long as I consent. (Since this work was done, Richard Pope has helped take this thinking on clear, simple data permissions much further.)

It wants to add me to the Data Protection Register, which is an important legislative requirement in the UK. And it wants to add me to the Register of Employers, because my new company might be employing people soon.

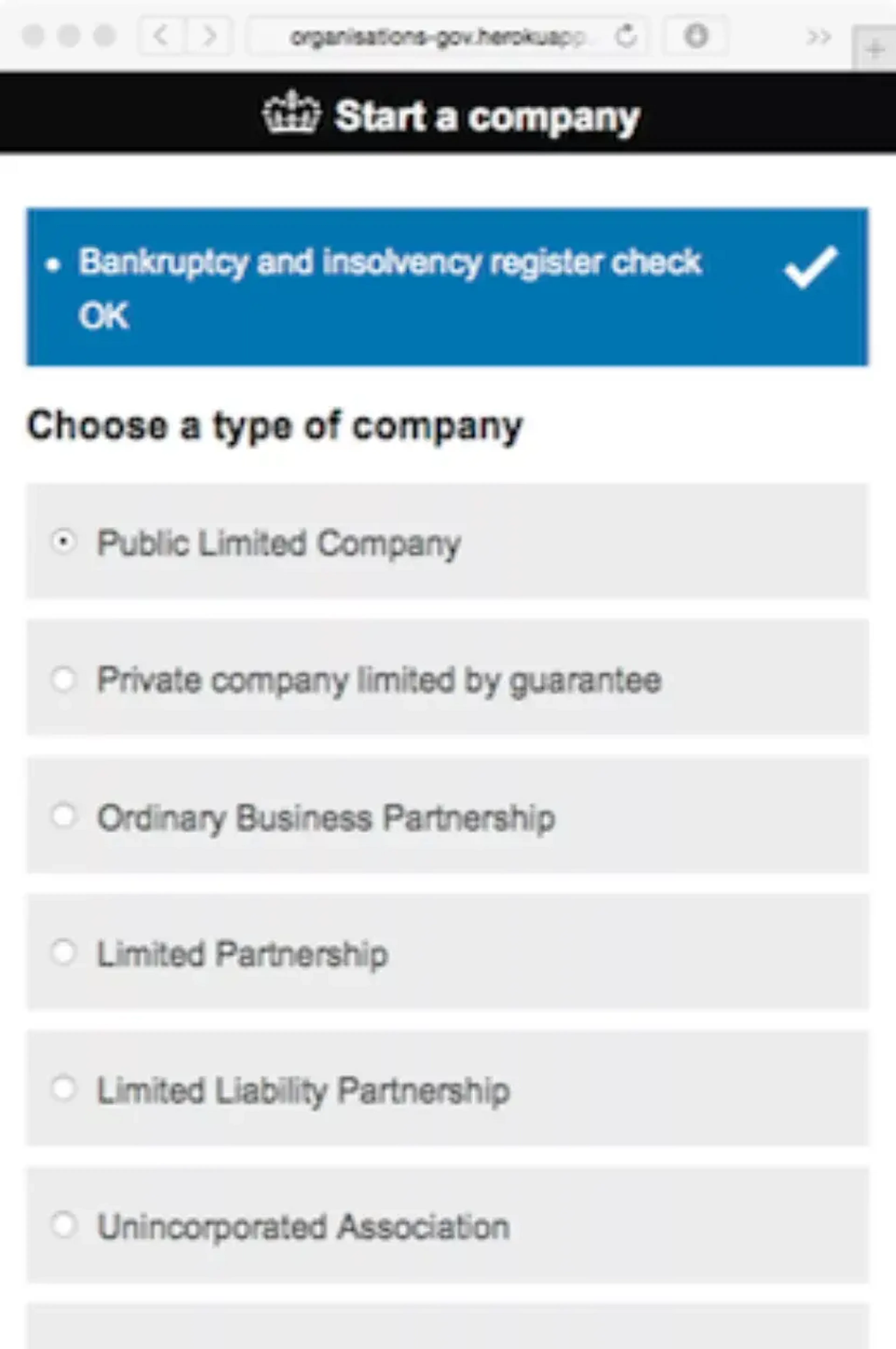

One click later, and the service has already done a lot of work for me. It’s confirmed that I’m not a bankrupt, on the Insolvency Register and hence barred from being a company director. That might seem like a small, simple thing, but at the moment it can take a long time for this check to be done, if it is done at all. At best, this leads to failure demand.

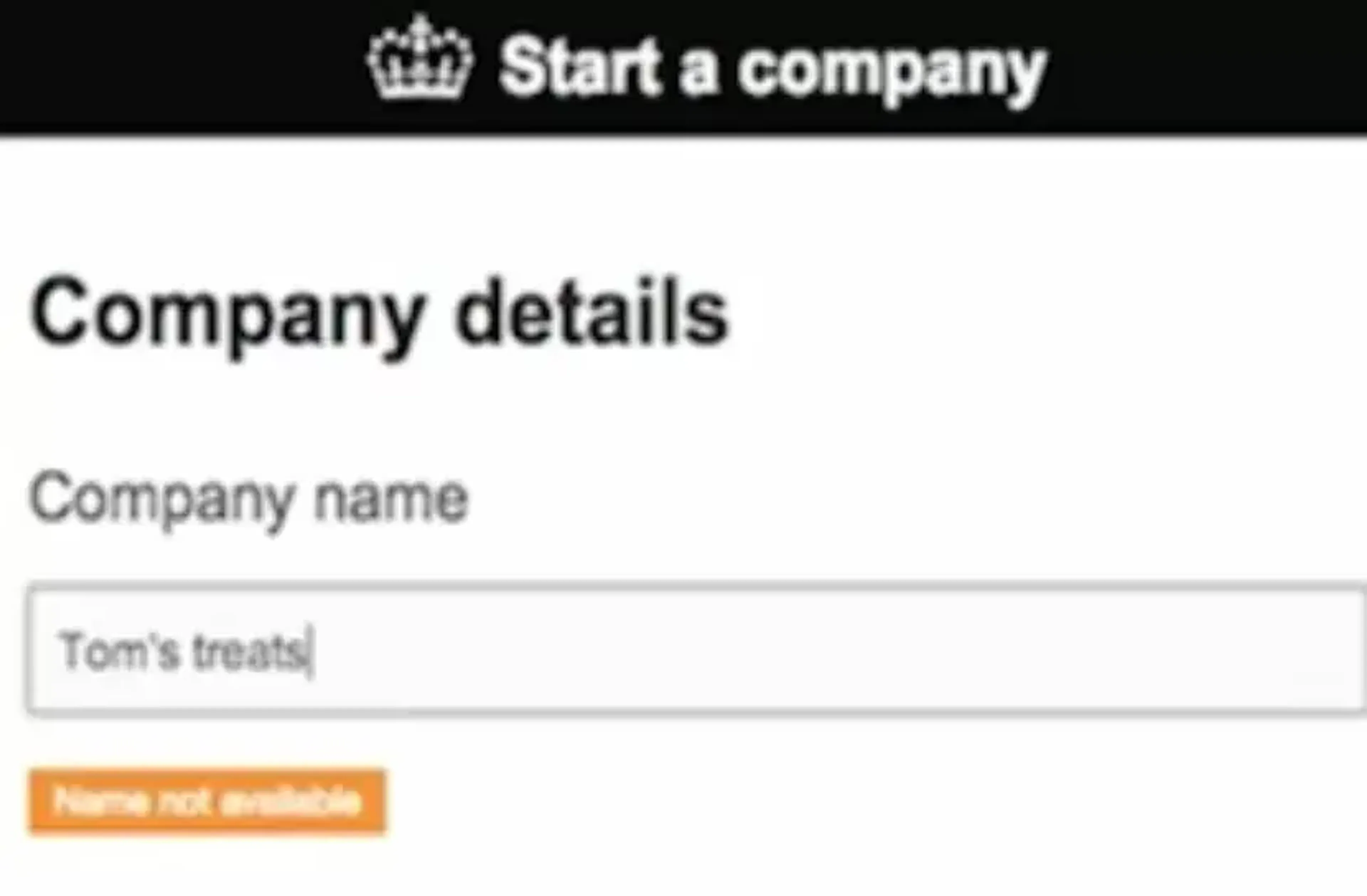

As well as limited companies, UK law allows all sorts of other entities to trade. It took our little project team about two weeks just to find the full list. Lots of companies end up getting set up the wrong way right from the start – again, failure demand. For now, I’m going to call my company “Tom’s Treats”, because I want to open a snack bar.

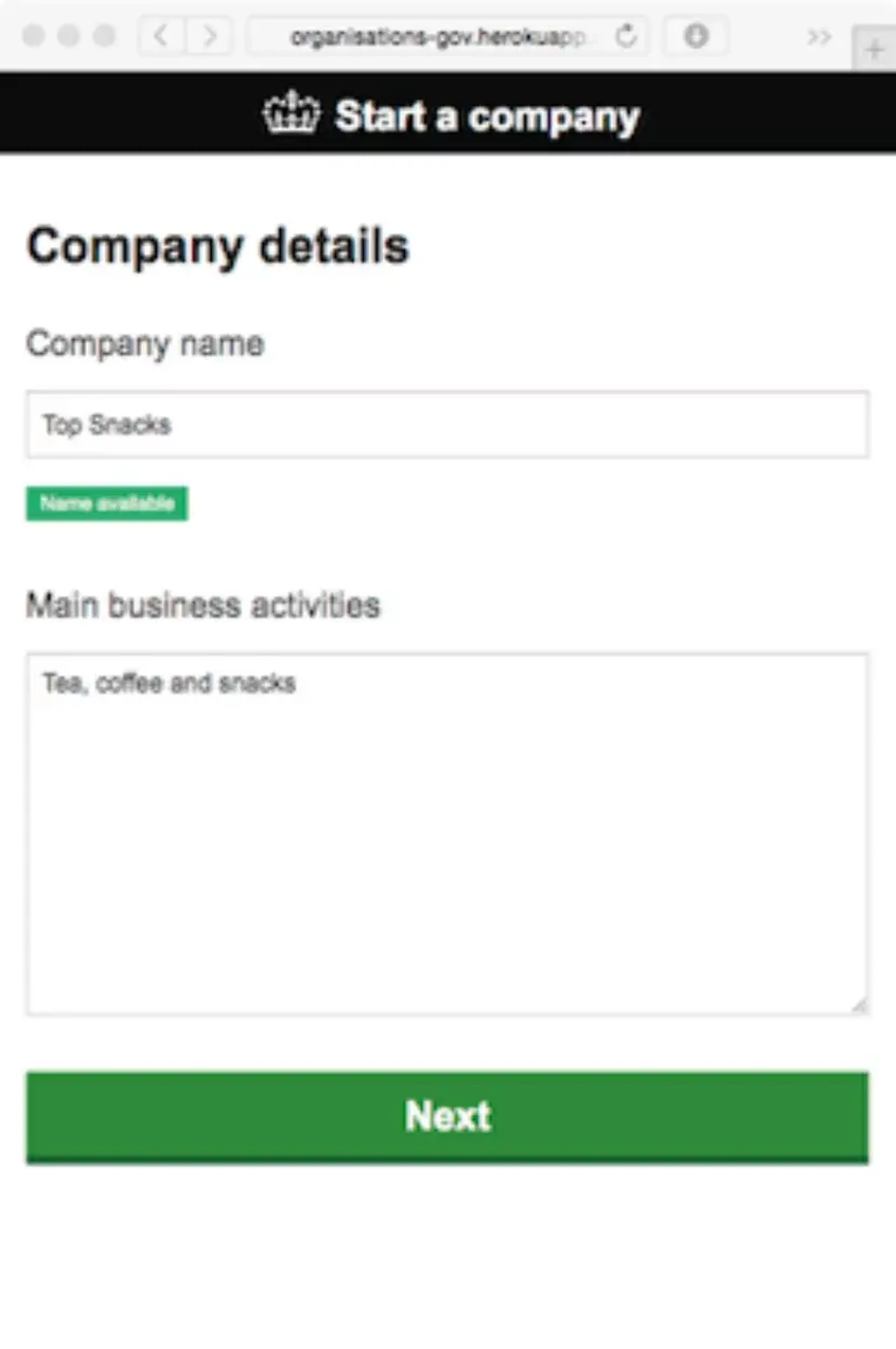

Again, because our service can access the right data, it tells me immediately that I can’t use the name “Tom’s Treats” because someone else is trading under that name. I’ll use the name “Top Snacks” instead.

It sounds like a little thing, but naming things properly is hard, and matters. In 2009, Companies House mixed up the name “Taylor & Sons” with the name “Taylor & Son”, declaring the wrong one had been wound up. As a result, a healthy company employing 250 people went bust in short order, and the subsequent court case left Companies House facing a compensation claim of over £8 million which was settled out of court.

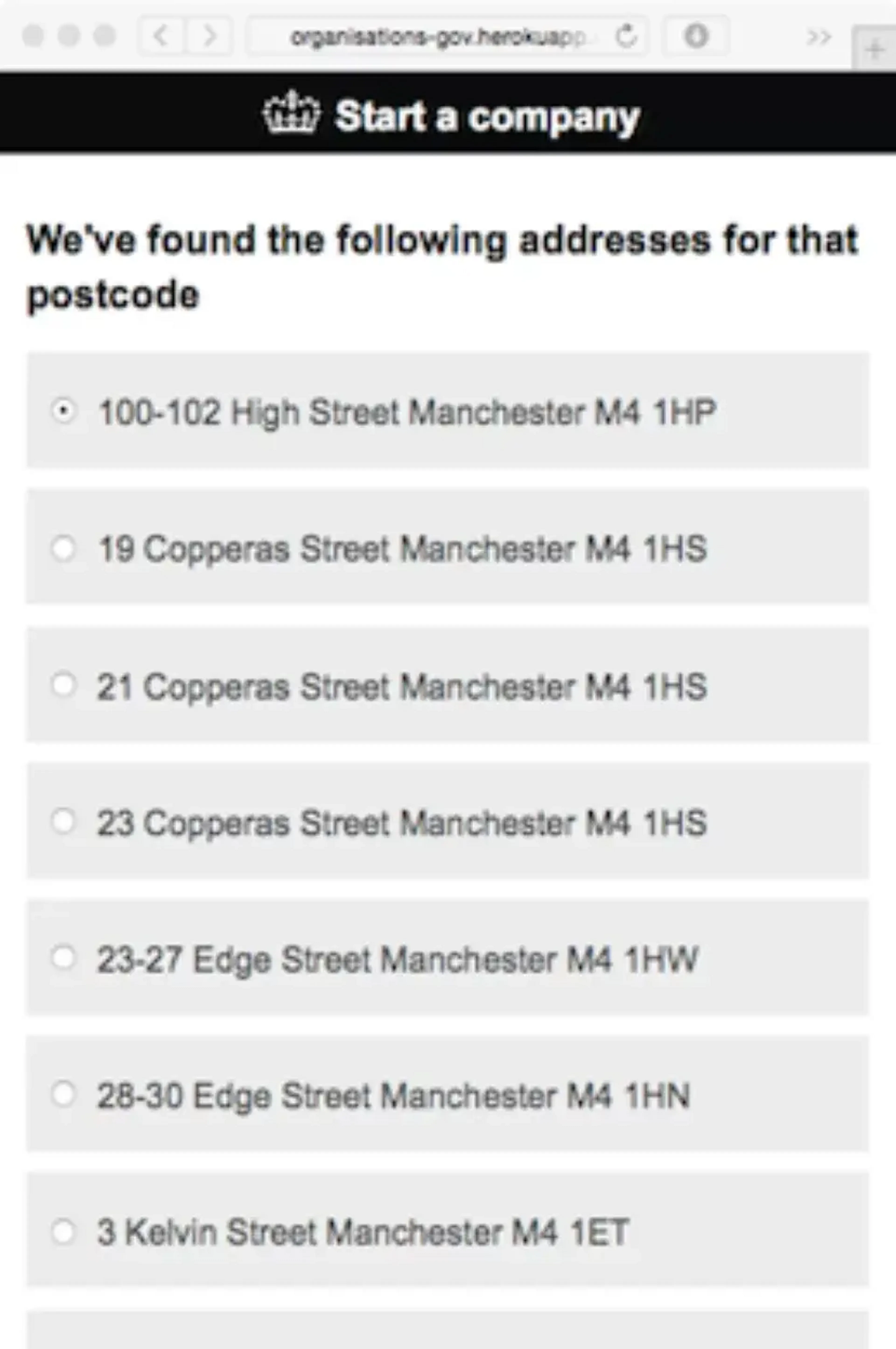

Every company needs a registered address, but rather than allowing me to type one in (and perhaps make a mistake), this service uses a simple address finder. Behind the scenes, there’s a register of addresses that makes this data easier to access and associate with me – because as a user, I’ve given my consent.

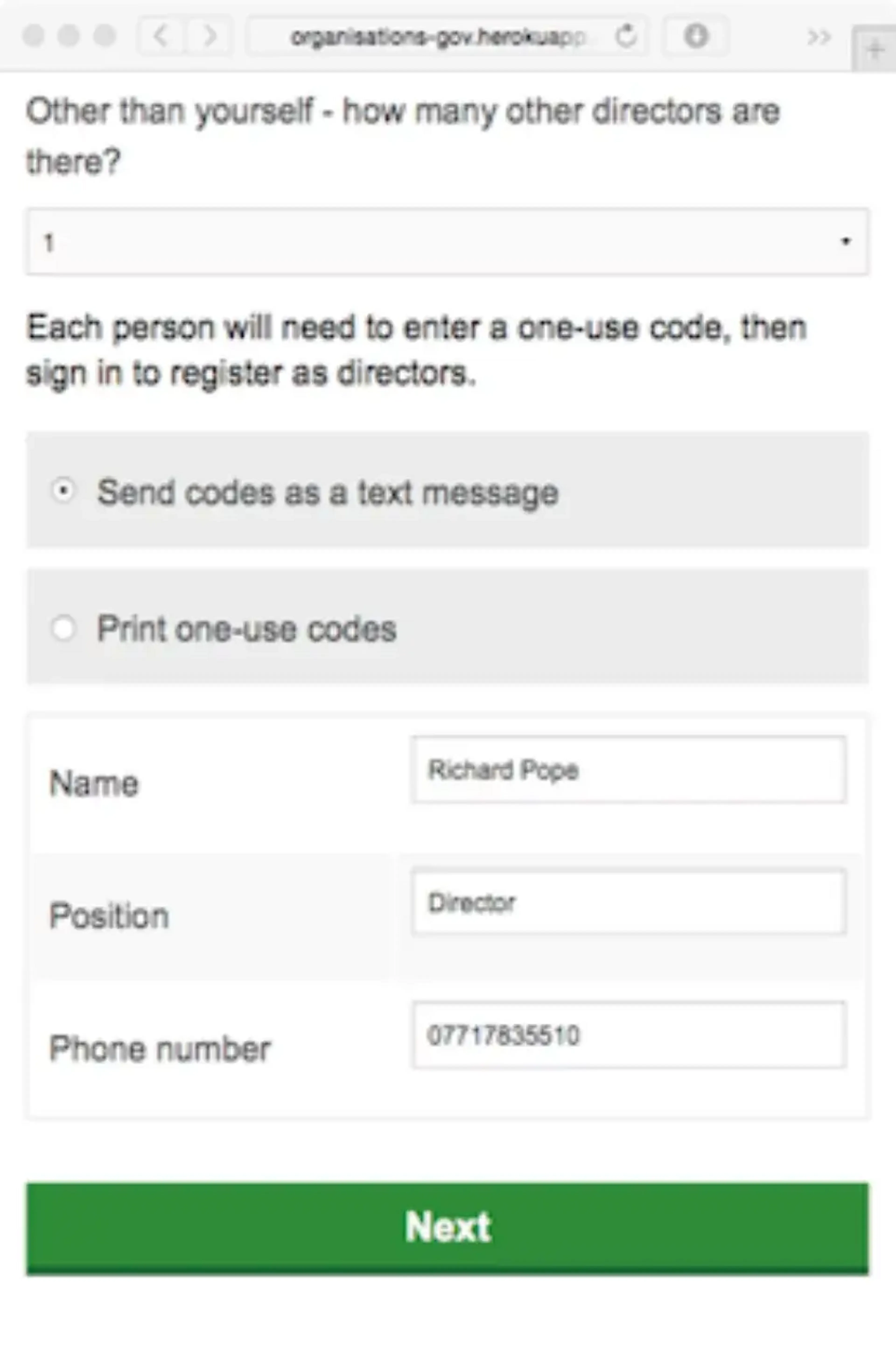

Most companies have more than one director, so the service asks about this too.

And it should make it easy for me, as a new company owner, to make sure my company is added to all the right registers. Notice that it doesn’t ask me “Which registers would you like to be added to?” because as a user, I shouldn’t be expected to know what they are. Users shouldn’t have to understand how government works in order to do the right thing. (Although, as Richard Pope has pointed out to me, that information shouldn’t be obfuscated from them either.)

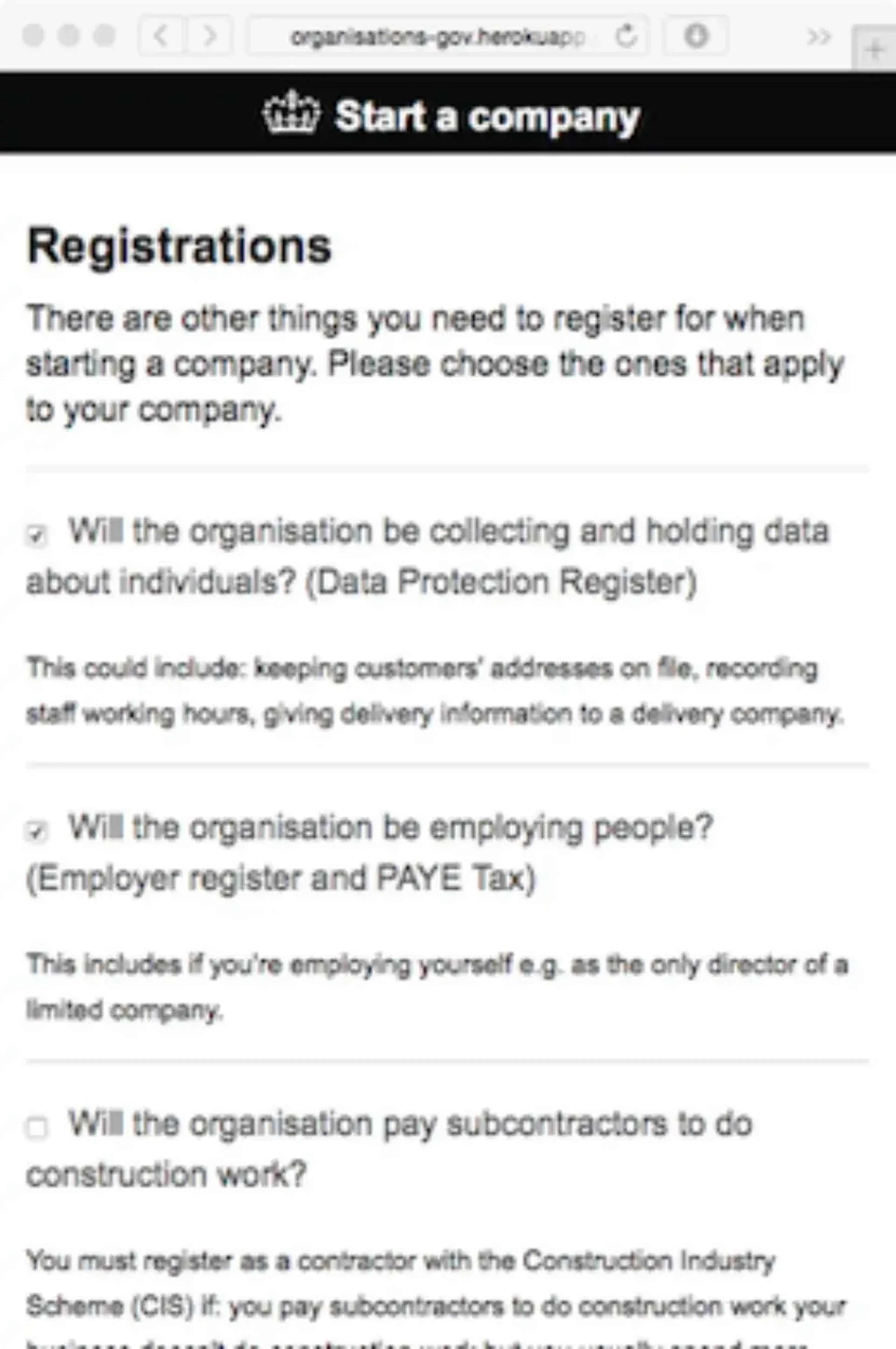

So instead, it just asks me simple questions – will I be collecting and holding data about people? Will I be employing people? Will I be paying subcontractors? All I have to do is tick some boxes, and my company will be added to the appropriate registers, depending on my answers.

The subcontracting question in this example is an interesting one. It only applies to companies in the construction sector, which are required by law to register the fact that they pay subcontractors. It’s a very niche need, and it doesn’t apply to my snack bar business, but this is one of probably hundreds of similar niche requirements.

Too often, business owners only know about these things after they’ve failed to comply with them. More failure demand, more friction, more stress for entrepreneurs, more dysfunctional lack of trust in government.

Just by ticking a few boxes, I’ve signed up to the right registers, and I don’t have to worry about that stuff anymore.

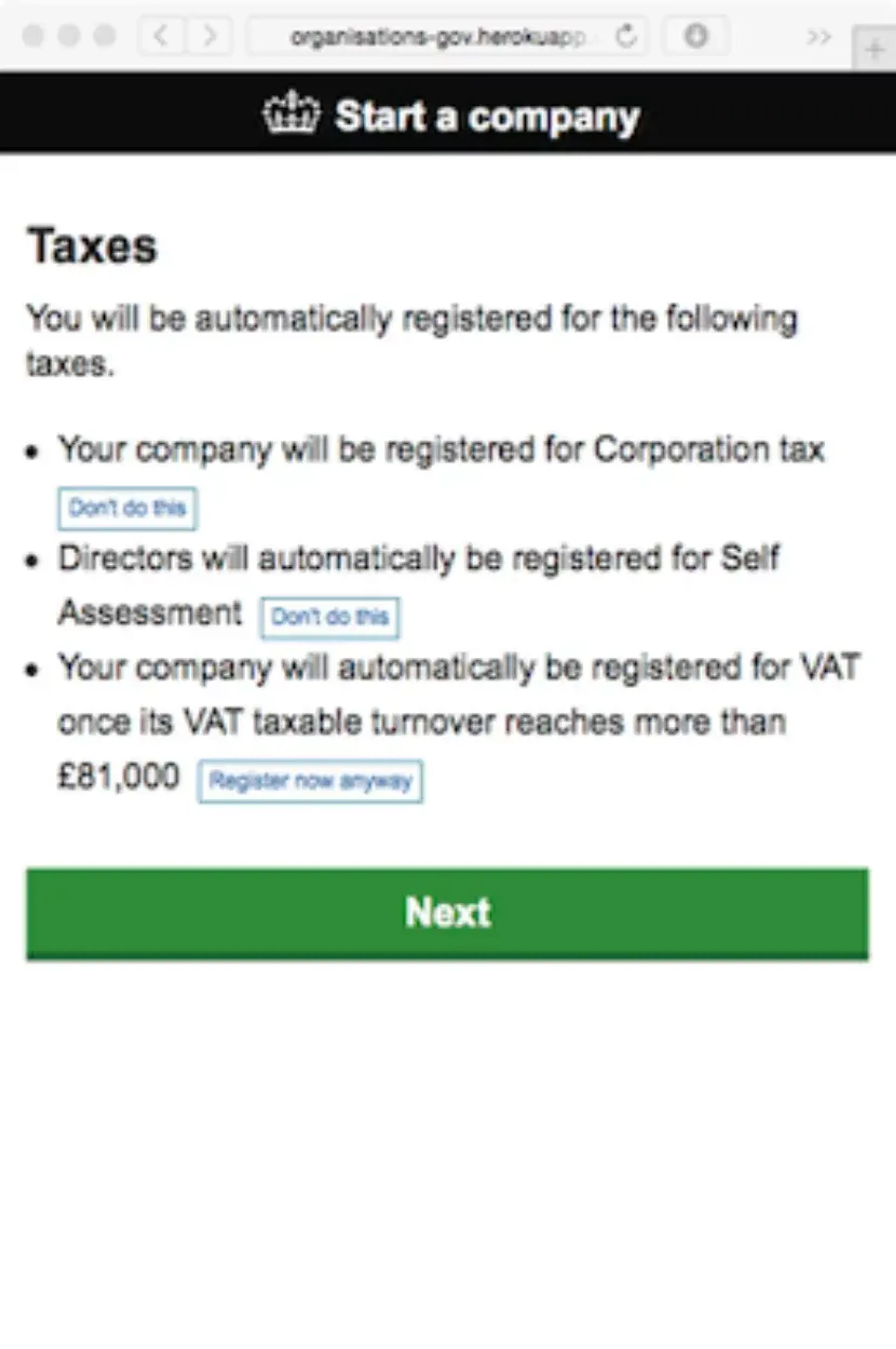

Now I need to sign up for taxes. Most normal companies in the UK have to sign up for three different taxes. They don’t really have much choice about this; it’s a legal requirement. So the service just makes that the default choice, and presents me with it. It tells me I’ll be registered for these three taxes automatically, and gives me a chance to opt out if I believe my business qualifies for some sort of exemption.

(Think of the potential for VAT, which only applies to businesses that cross a certain turnover threshold: in this imaginary future world, It’s not up to me to work out if I have to sign up for VAT, because government uses its data to register me at the right time. My accounting software could even check an API periodically, or register for a notification, and adapt automatically.)

Of course, both sides of this transaction – myself as the business owner, and the government – need to have proof that I’ve gone through this setting-up process and made the decisions I made. There has to be a verifiable, immutable record of what we’ve agreed so that, if something goes wrong in future either the business owner or the government can point to an audit log of the precise process that was followed.

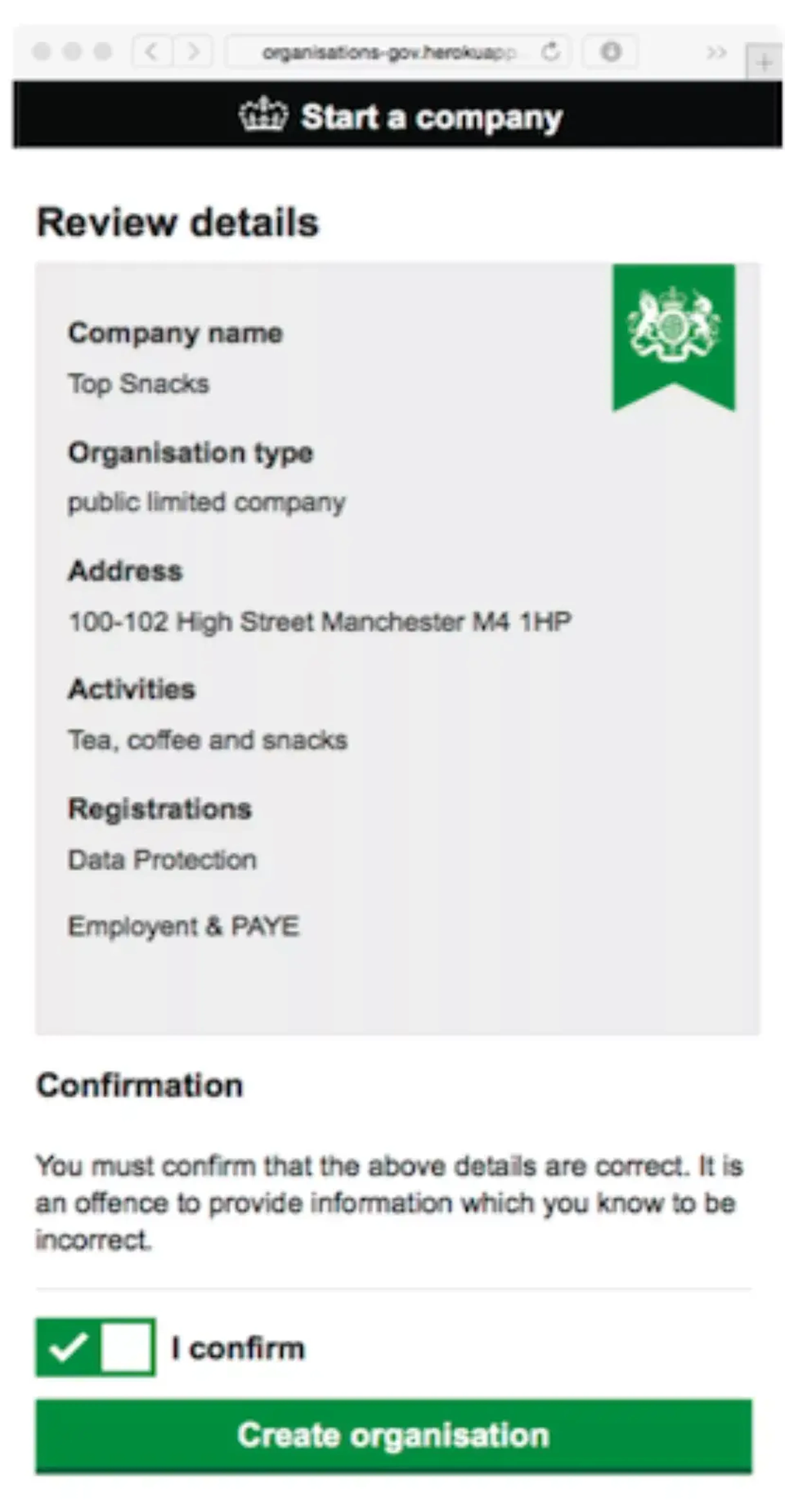

And it’s done. This is how I could start a new company. It would only take a few minutes.

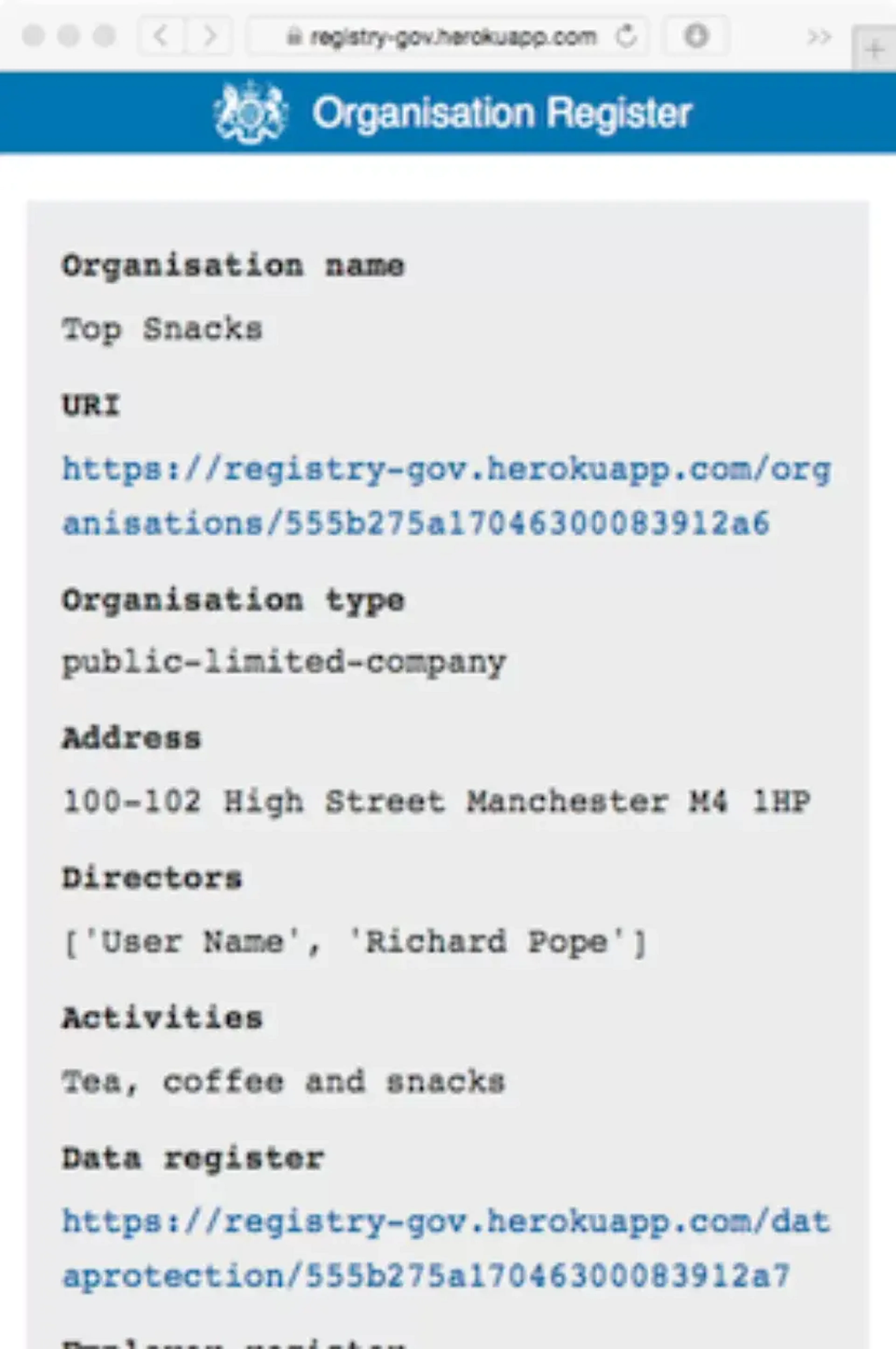

The data has been recorded in the Company Register. I can go to a web page and see the raw data in the register about my own company.

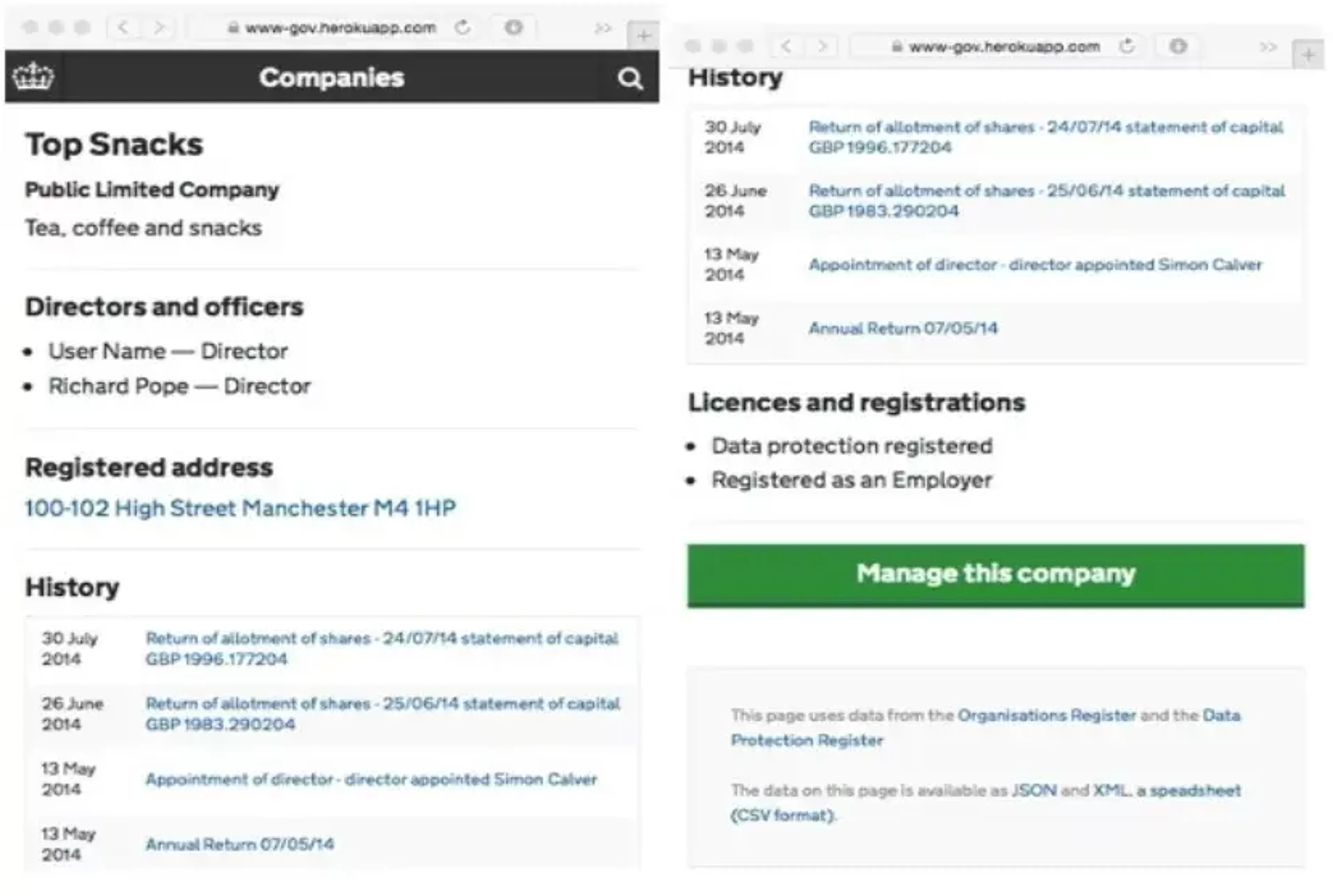

And here it is: “Top Snacks.” The page shows open data about my company, its registered address, its history.

This is what registers look like. This is how they work. They use the web to share data.

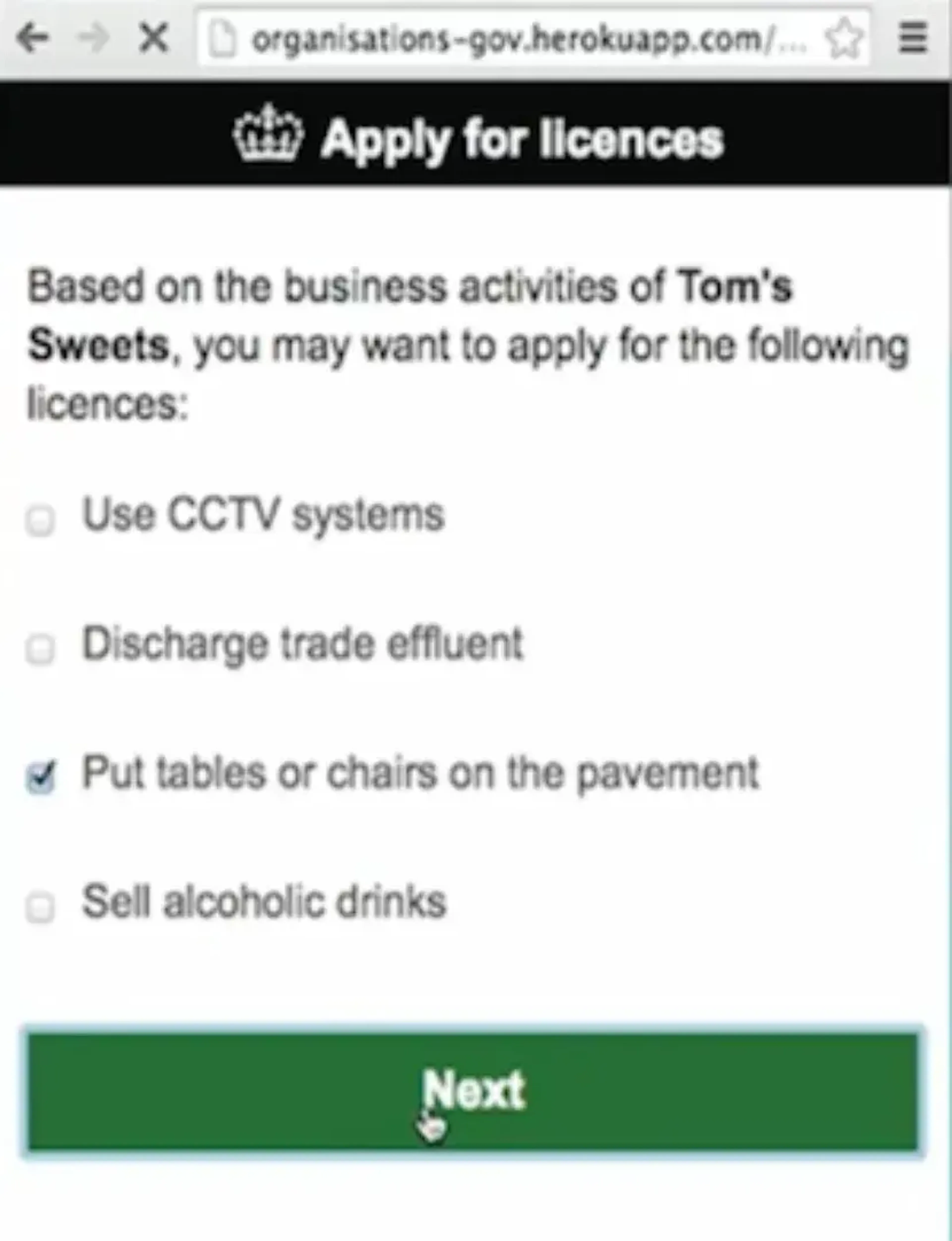

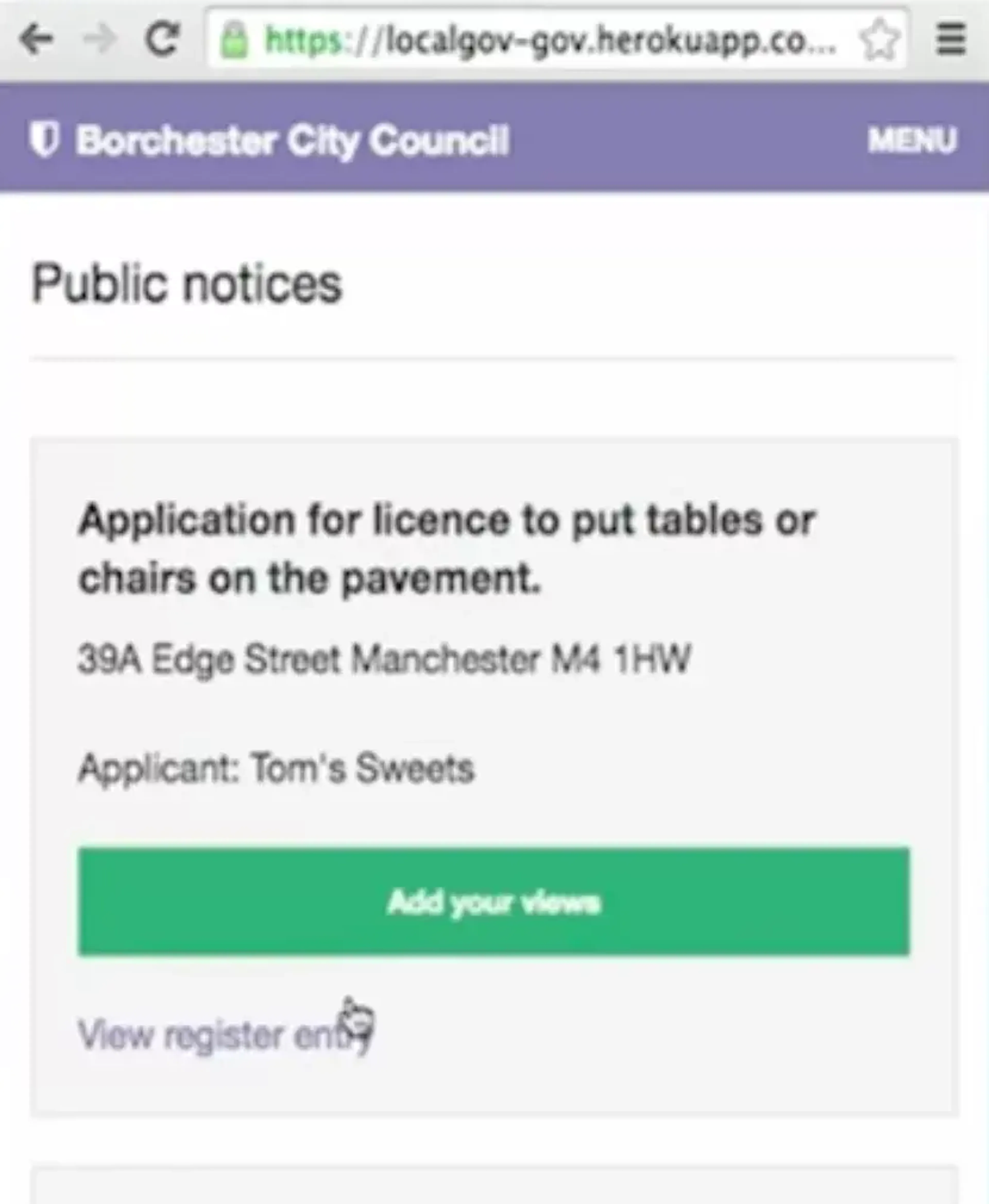

Now, let’s imagine I’ve been running my snack bar for a few months and everything’s going great. So I want to expand, pull in more customers. And I have an idea: I’ll put some tables and chairs on the street outside, and serve hot drinks. But I need a licence to put furniture out on the street, and that licence comes from local authority, not from the national government.

In our natively digital nation, that’s not a problem. Once again, I assert my identity as a director, and the service gives me the chance to apply for all sorts of licences.

I pick the “Put chairs and tables on the pavement” option and click Next. The service asks which address this is for – remember, it already knows where my shop is, because I told it when I set up the business.

And the application is done. (This screenshot shows the wrong business name – told you some of these screenshots were a bit out of date.)

It’s been sent to the Federated Notices Register that my local authority contributes to, Borchester City Council. And here on their website, we can see an official public notice of my licence application. Members of the local community can comment on it, if they wish.

Suddenly, elegantly, and with consent, we have spanned across both central and local government services. Thanks entirely to the ecosystem of services, platforms and data.

Let’s look at another detailed example.

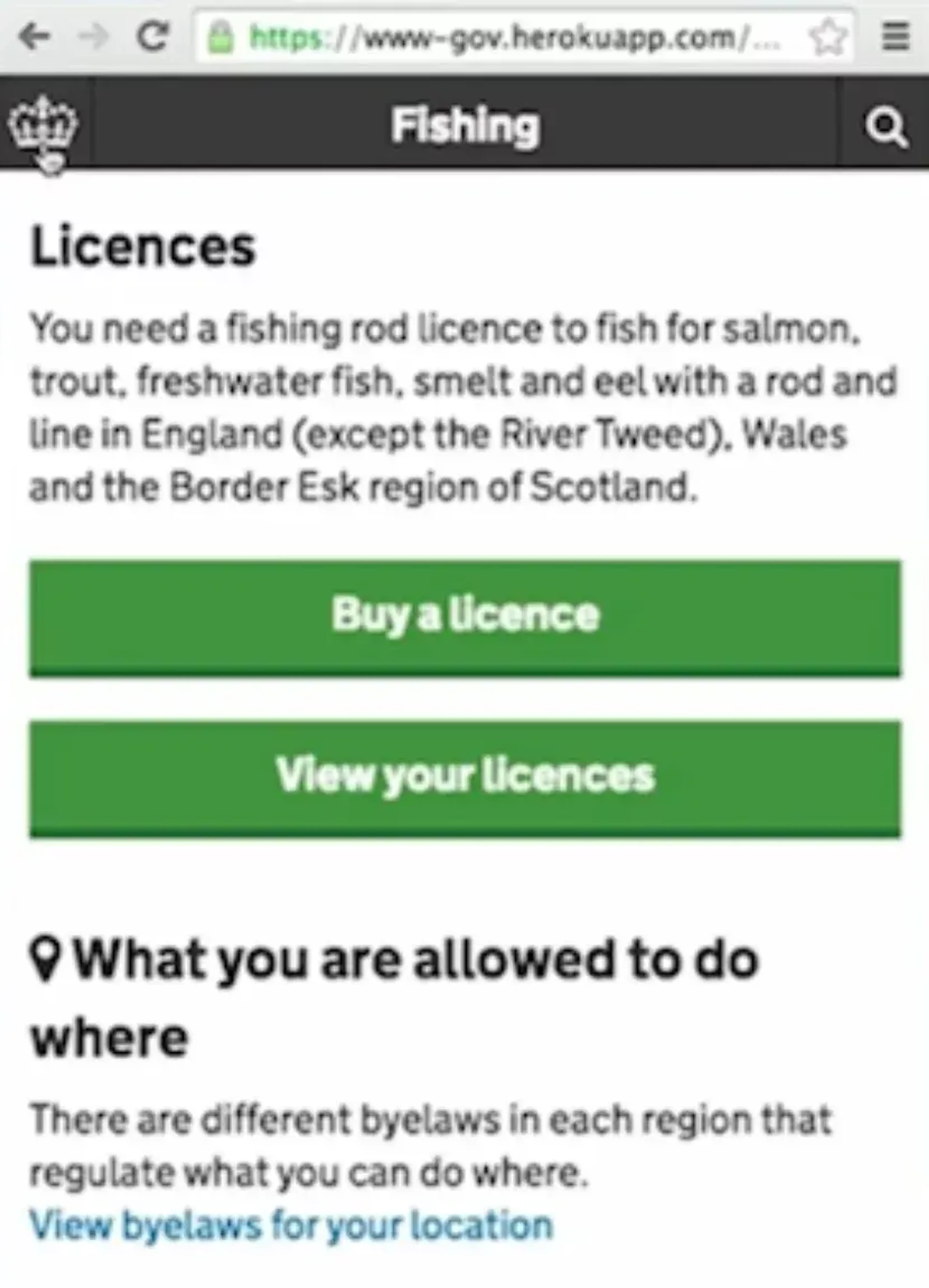

If you want to go fishing in the UK, you have to get a rod licence. It doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it’s a very popular service with hundreds of thousands of transactions per month. Since I gave the talk in 2015 the UK fishing licence has been digitised. It’s well done, and uses the UK’s new and highly successful GOV.UK Notify platform to send users a digital licence via email and/or text message.

But our imaginary future world offers some other interesting possibilities. So let’s have a look at them.

There’s a minister who’s accountable and responsible for the policies behind this service. We should make that clear. We can do it simply just by adding a link.

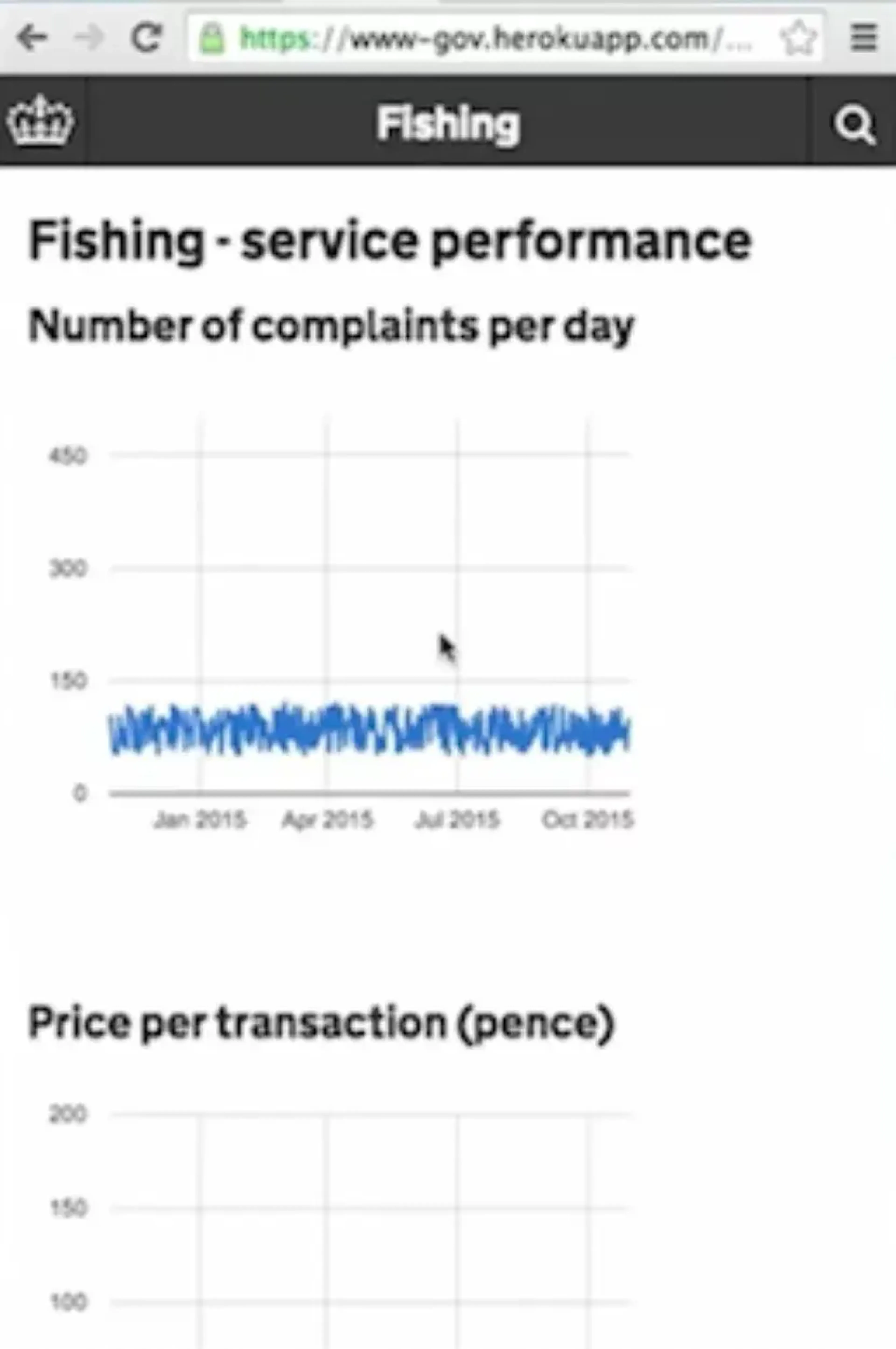

We can show people the performance of this service, as part of the service itself. Simple metrics such as how many complaints come in per day, the price per transaction, the number of prosecutions, the number of licences. All this can be part of the service – think of it as accountability at point of use. This is not an add-on, this is not management information; this is being a democratic service in the 21st century.

We can show the legislation that underpins this service. Again, all it needs is a link. Not everybody will want to follow it, but we have an obligation to make that legislative link clear for those that do. For example, if someone thinks they are being wrongly prosecuted for not having a fishing licence, they should be able to see what law applied from within the service itself.

We should make it easy for people to give feedback about a service. Holding an annual general meeting for each and every public service would be a step forward in accountability.

And we should make it easy for the service manager in charge to communicate directly to users. That could be a simple as giving them a blog, and making it easy for users to find.

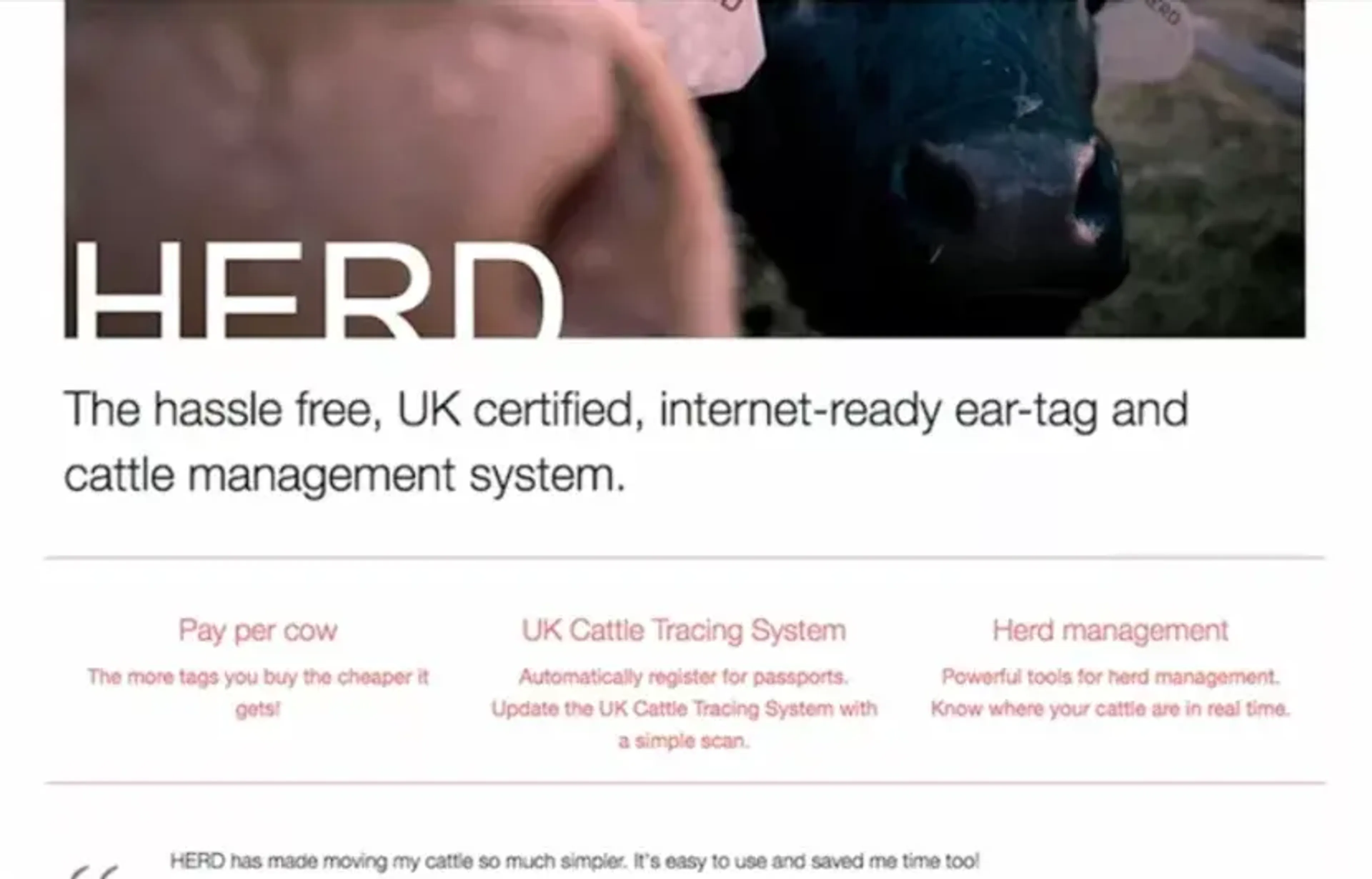

This is my last example. And possibly the most radical idea, long term. How to allow the commercial and third sector to offer or integrate with public services, while retaining democratic accountability?

Let’s start with cows. In the UK, the law says that if you move livestock from one place to another, you have to record that fact with the British Cattle Movement Service. In the event of a disease outbreak, there is a record of which animals have been where, and the authorities can contain the spread of the disease much more easily.

At the moment, it’s hard for farmers to do what the law requires them to do. It needn’t be. It shouldn’t be.

Why don’t we just treat it like a register, get the consent model right, and embrace the fact that there’s already a whole bunch of “internet of cows” businesses out there selling digital tools to cattle farmers?

A register like this might not even need a user-facing interface. It could be included as a free feature in existing commercial cow monitoring services, via a properly audited API. The UK’s HMRC already follows just such an “API access only” approach for some of their more esoteric business taxes.

This points towards a very big idea. That government provides APIs, platforms, standards and data which not only improve public services, but which can also be relied on by a jurisdiction’s private and 3rd sectors. Government providing a solid, reliable suite of Internet-era infrastructure on top of which both public and private value can flourish.

Government as a platform; not just government on a platform.

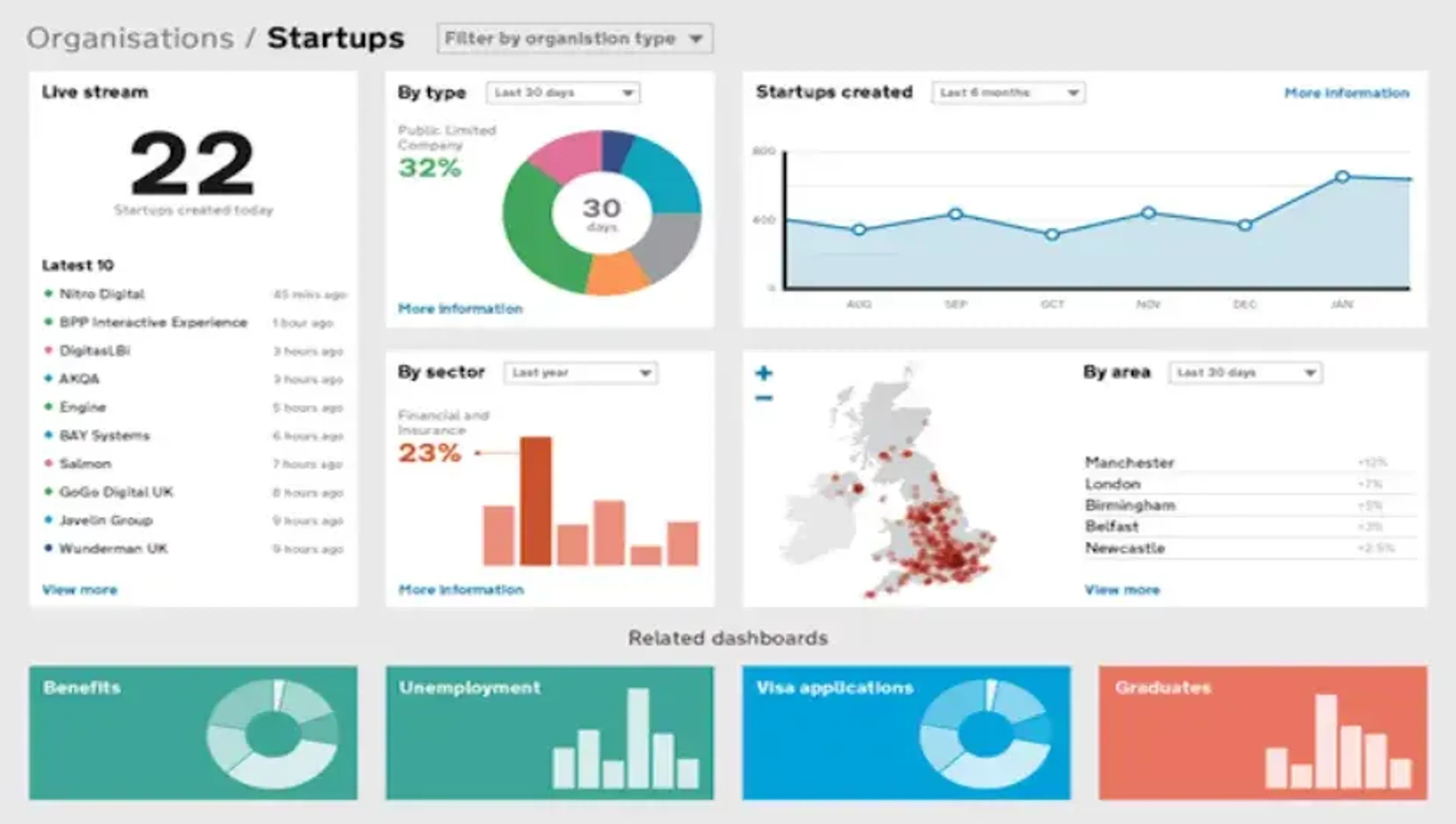

Building infrastructure like this means we could build real-time information dashboards that tell ministers whether their policies are working.

Little like this exists at the moment. Too often, ministers and civil servants are making decisions based on hunches and guesswork. They have no choice – they’re flying blind because of the lack of timely, joined-up data. In a digital nation, we could provide the useful feedback loops they need, to help them gauge how well a particular service is meeting the policy intent behind it.

These dashboards could exist for many topics, with the underlying data (suitably anonymised) easily available for analysis by all. The UK Office of National Statistics have been doing great work building out their APIs, but that would be revolutionised if the data were genuinely real-time and not constrained by departmental silos.

Services

are required to use the trust and consent infrastructure appropriate to

the personal information they’re requesting. The fishing service needs

to know your name and your age, and it wants to know about any existing

rod licences you’ve got. But that’s pretty much it. We should be

transparent about the minimum viable data that each service depends on.

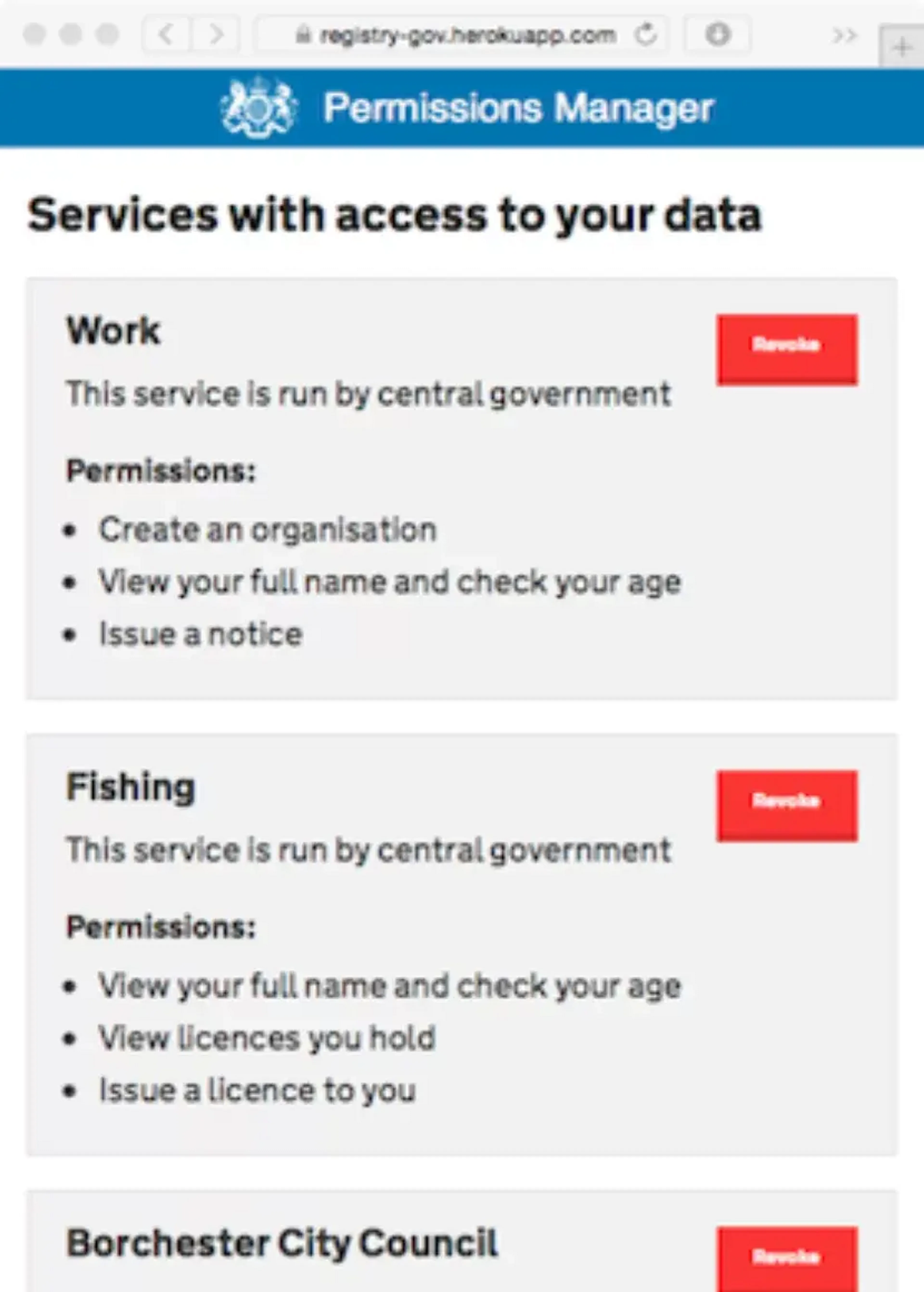

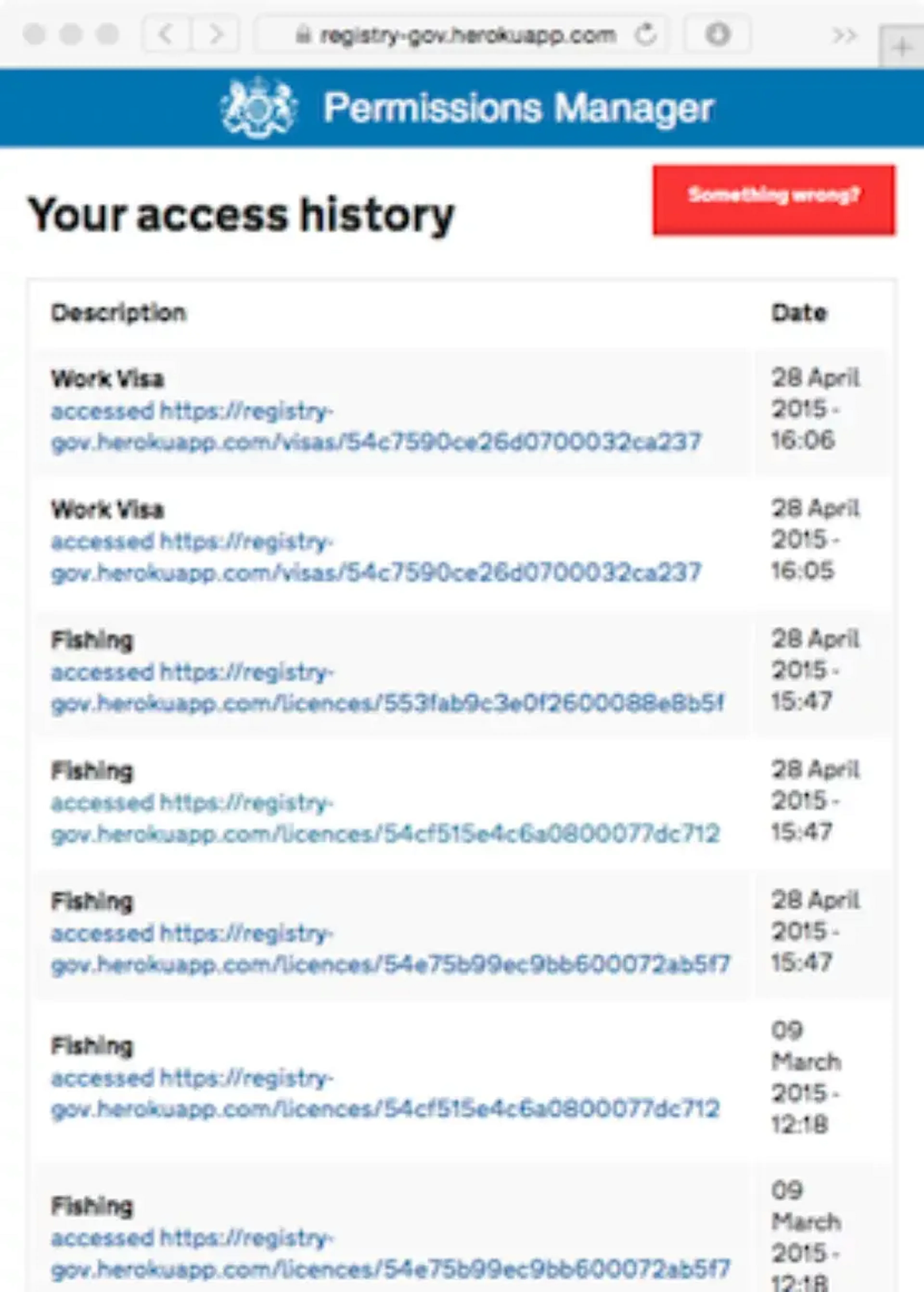

Users should be able to see which services they have granted consent to, and what data those services have access to.

Users should be empowered to revoke access to data they own, at any time. Or if it’s data about them, they should be able to see what it’s being used for, with some exceptions. Of course, revoking access might make it harder to start a business or get a parking permit or a fishing rod licence, but that’s the whole point of the trust and consent layer in our model. Users have control. Without that control, there can never be genuine trust, and the whole system breaks down.

Users should be able to see which services are accessing what data. Not just because it’s the right thing to do in a digital democracy, but because if you want a properly secure ecosystem, your users are the first people who will notice something wrong, and hit the button that raises an alarm.

One of the reasons I left government was because very few politicians or senior civil servants are willing to spend the political capital required to make a natively digital nation a reality in the UK.

It’s not about the money. In the UK, we could all of this for less than it costs to run our tax or welfare system for one year.

The biggest cost is the political capital to challenge existing institutional silos, closed mind-sets, and entrenched power bases. As a politician or as a senior civil service leader, you are going to have to cause a lot of pain for a lot of people to be able to realise this dream. Very few will take the risk. That’s what’s holding us back.

I believe that for the first nation to do it, the prize will be huge.

Estonia faced a crisis on its independence from the USSR in 1991, which left its institutions and infrastructure in a parlous state. This proved the catalyst for them to reinvent their institutional and infrastructural architecture along a model that is closest to that described above. Hence their ability to launch truly innovative ideas such as e-residency, which enables non-Estonians to start and manage a company from anywhere in the world, through access to Estonian e-services.

To make things like that happen, we need leaders who are bold. Who are willing to spend that political capital, and invest in creating the new institutions necessary to tie it all together. Boldness, as Janet Hughes wrote up so passionately, is something that should be baked into the values of the civil service.Be bold enough to build those new institutions. Be bold and brave, and build yourself a natively digital government. Claim the prize that awaits.

All of that is what I said during my Code for America talk, several years ago.

As I pointed out at the start, it’s a marker for where our thinking was at the time. We’ve had some time to think some more since then. I don’t claim to have a lot of answers, but I have been thinking about questions – questions that keep returning to me as a result of spending time with that small team, and devoting time to really thinking about how this all fits together.

Among the questions I’ve come up with are these:

I welcome your feedback on this essay and the questions above. Please comment below, or via Twitter on @tomskitomski.

Here’s a demo that shows the digital state in action. Let’s look at a fictional new service from central government: buying a fishing licence. First, you start at GOV.UK, just as you would for any other government service. Then you have to confirm your identity. This demo shows a fictional identity platform, but we expect GOV.UK Verify to do this task. You enter your details, and you’re signed in.

Next, the service asks for your permission to access data about you held in registers: name, age, and any existing licences you hold – just those things and nothing else. You grant permission with one tap. Straightaway, the service knows you’re old enough for an adult fishing licence, because you granted permission.

There are a few more details to fill in, depending on what licence you need, and now you have to pay for your fishing licence. This is a cross-government payments platform. It looks and works the same across many different services. A few more taps and it’s done. Here’s your digital fishing licence. You can save a copy on your phone and show it whenever you need to.

Another example: this is a parking permit service from a fictional local authority. Again, you have to confirm your identity. It works just the same way as before. Now the service asks permission to see some data. In this case, it’s your home address and details of cars you own – just those things and nothing else.

Straightaway, the service knows which car needs the permit and where it will be parked. The fee is calculated instantly, and all this happens because you granted permission for the service to see data about you.

Now you just have to pay for your permit. This is the same payments platform that we saw last time. A few more taps and it’s done. Here’s your copy of the parking permit. The local authority automatically knows your car is covered. There’s no need to display a paper permit in the car window.

Founder