Technology review

We help organisations develop a responsive, resilient and sustainable approach to their technology.

Every organisation needs to be good at technology.

That’s why we always tell our clients they need an internet-era CTO. But what does that really mean? What does it look like?

An internet-era CTO is able to understand what should be hard and what should be easy, and stay up to date with how that’s changing. Doing experimental data analysis (even on lots of data) is pretty easy, fixing how you manage data responsibly is hard. Taking credit card payments is now easy, scaling to handle a serious Black Friday surge is hard.

With that understanding, they should work on making sure that the things that should be easy actually are, and on making the hard things easier.

You can see what an internet-era CTO can achieve by looking at internet-native successes; constant innovations from Amazon’s web services, microservices architectures and empowered teams at Netflix, or the “code as craft” approach of Etsy.

How do we make practical comparisons with global organisations like those? Here are my suggestions of characteristics to test ourselves against:

Organisations need to be equipped to respond to constant change. Being good at technology means having confidence in our ability to anticipate those changes, and respond to them well.

These are the scenarios I like to ask about:

When a new idea occurs to you, or you want to trial a change, can you:

When a new technology comes along, do you:

When something goes wrong, can you:

Regardless of what else is going on, do you:

Within each of those things there’s a constant balance between being able to respond, and proactively finding opportunities. And every one of those things emerges from effective teams.

At IDEO’s Make Change Happen event (which we attended, and Mike Bracken spoke at) back in October 2018, Paul Clarke, CTO of Ocado, talked about the importance of focusing on the skills and competencies in your team: “Competencies take a long time to develop, but they far outweigh the outcomes along the way,” he said.

Competencies are more important than code.

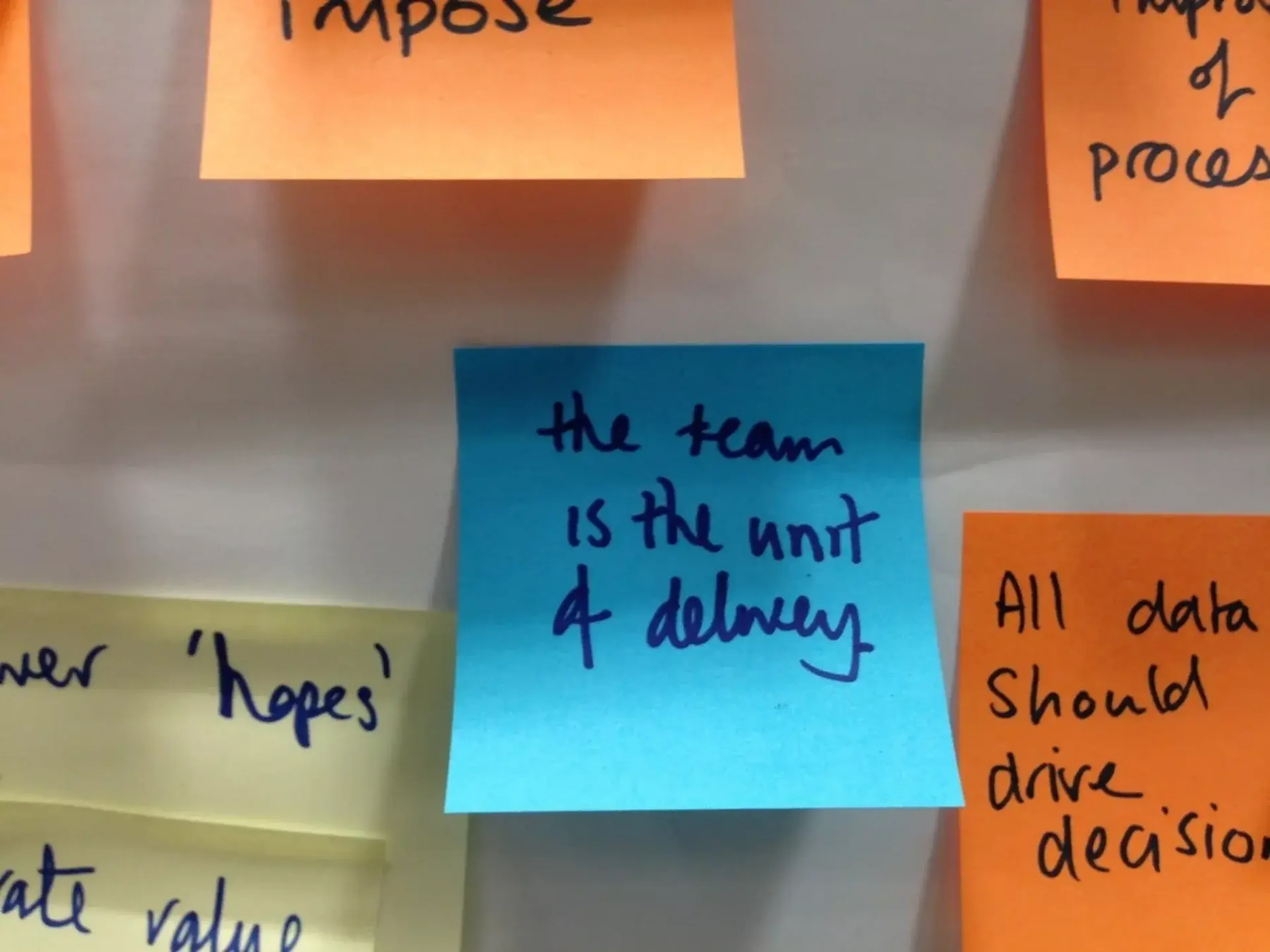

Organisations that are good at technology have the right teams in place. They give those teams space and incentives to keep building their capabilities. Doing that lets you do these things Tom Loosemore called out in his internet-era ways of working post:

When doing that you’ll remember that technology itself is very rarely where the asset or value lies. It’s in what you deliver for your users, the capabilities in the team, and the data you collect.

Most of the time technology is managed in silos. We build an IT team, then a department, and then a division. And in almost every case we’ve built that around the dominant personality types in technology – using structure and stability as a means to reduce risk. In most cases, that leads to stasis rather than stability.

In his book WTF?, Tim O’Reilly talks about the desire to produce maps to understand an environment or a concept. In itself, that’s not a bad thing and the conversations involved in producing maps (like Wardley Maps) can be really helpful, but reality is often less clear:

“Most often, in fast-moving fields like science and technology, maps are wrong simply because so much is unknown. Each entrepreneur, each inventor, is also an explorer, trying to make sense of what’s possible, what works and what doesn’t, and how to move forward.”

That exploration’s not something that any one discipline can do alone. Being good at technology means having the tools and the confidence to collaborate in navigating a constantly changing environment. Having the confidence not to focus inwardly on the technology, but more widely at how it affects people: practically and ethically.

Being good at technology means having the tools and the confidence to collaborate in navigating a constantly changing environment.

It can be attractive to think that we can buy an IT solution to a business problem (things like HR processes, procurement management, or logistics) but business activities always involve a range of people and we can only use technologies to their full potential if we work alongside those people as part of a team.

Partner and CTO